Tomorrow night, the famed basketball rivals meet again. Fans in North Carolina and across the country will don their Duke or Carolina blue and gather to watch the game. And Duke’s Cameron Crazies will go crazy, carrying on the tradition of post-game celebrations and bonfires.

Although Duke students were lighting bonfires to celebrate the annual Duke-UNC football game decades ago, the tradition of marking major basketball games with a blaze is of a newer vintage. The newly-processed Duke University Police Department Records provide insight into this period of history.

According to the records, Duke’s bonfire and bench-burning tradition began in 1986, when there was a large screen set up on the quad for students to watch the NCAA final game between Duke and Louisville. Duke lost, and a few angry spectators reacted with assaults and vandalism. The Police Department was unprepared for such a result, but learned from the experience. During the 1990 tournament, the Police Department opted for a more controlled option of a large screen in Cameron for the Duke vs. UNLV game, with a Duke ID card required to enter. They also sponsored a bonfire in the Card Gym parking lot—with no idea this would set the precedent for a beloved tradition—but few students braved the bad weather.

1991 was an explosive and fiery year: after the watching the game between Duke vs. UNC on screen in Cameron Stadium, students spontaneously set up a mudslide and multiple bonfires. Planned fires for subsequent games burned too big and were too crowded. Duke Police had prepared with stadium evacuation plans and ambulances on standby, but were unprepared for the intensity of student energy—often directed harmlessly, but occasionally leading to violence.

Following the Duke-UNC game and some student injuries, Director of Public Safety Paul Dumas worried for students’ safety during the post-game celebrations. The Police Department organized a special committee to establish policies regulating the bonfires, but as many a Chronicle editorial pointed out, these well-intentioned regulations were difficult or impossible to enforce. For example, a March 25, 1991 editorial noted, “Parts of the policy are ridiculous. Why would a living group ever ‘contribute its bench willingly’ to the fire, as the policy suggests? In reality, the first partiers who get to the quad determine which bench gets sacrificed.”

1992 was even more out of control: many games were followed by unauthorized fires on various quads around campus, as well as some break-ins and emergency room visits. In 1994, the Police Department decided not to support any bonfires despite numerous student petitions, and began citing students for starting unpermitted fires. Yet the momentum was building; Duke was now expected to make it to the national championships each year, and, with memories of bonfires and bench-burnings from previous years, students wanted to celebrate in their own way.

Over the next few years, students insisted on commemorating games with bench burnings, and student-administration tensions increased. During the 1998 season, twenty-five students were arrested for disorderly conduct and starting unauthorized fires, while student editorials accused police of excessive force when responding to unauthorized fires. That year, the administration refused to allow the traditional bonfires and planned giant foam parties instead to celebrate major victories–unsurprisingly, most students were not enthused. In a February 5, 1998 Chronicle article titled “Students reject foam, beg for fire,” freshmen expressed disappointment about missing out on an established tradition and upperclassmen also rejected the plan: “the administration’s heart is in the right place, but foam is kind of a moronic idea.”

Three days after the Duke-UNC game, on March 3, 1998 students burned many benches despite regulations, strategically organizing a decoy to draw police attention away from the real fire. A quote from a Chronicle article following the incident states eloquently: “They took away our alcohol, and we stood by and watched. Then they took away our housing, and we stood by and watched. Then they tried to take away our bonfires, and we went to war.” It was a clever display of student unity to fight back against the administration’s perceived encroachment on their rights, and it worked: the administration sanctioned bonfires and bench burning as long as it adhered to city fire codes.

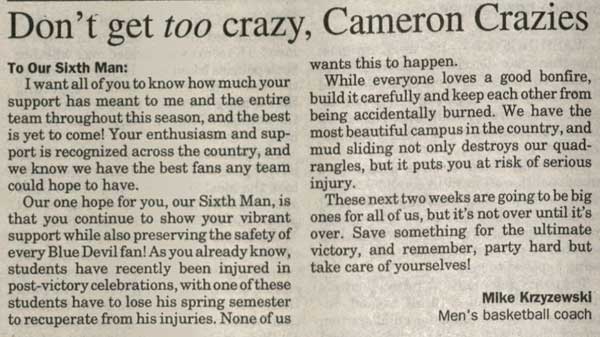

Duke Police adapted from year to year and recognized a trend of increasingly intense—and, for a few people, dangerous—parties. They tried to engage in public awareness campaigns by requesting support from the University President, Vice Presidents, student government, and Coach K, to encourage safe behavior. The department also began partnering with the Durham Police Department and the highway patrol to enlist enough officers. Yet there was only so much they could do to prevent injury or crime. And, while the police records focus on the number of incidents of injuries or assaults, most students had a good time celebrating their basketball team. It’s an interesting lesson on perspective: depending on your vantage point, you might see the bonfires of the 1990s as riots or as celebrations. Either way, the seeds of a tradition were planted. So whether or not you gather around a bonfire on February 18, enjoy a safe and exciting game!

Post contributed by Jamie Burns, Isobel Craven Drill Intern, Duke University Archives.