Post contributed by Mary Mellon, William E. King Intern for the Duke University Archives.

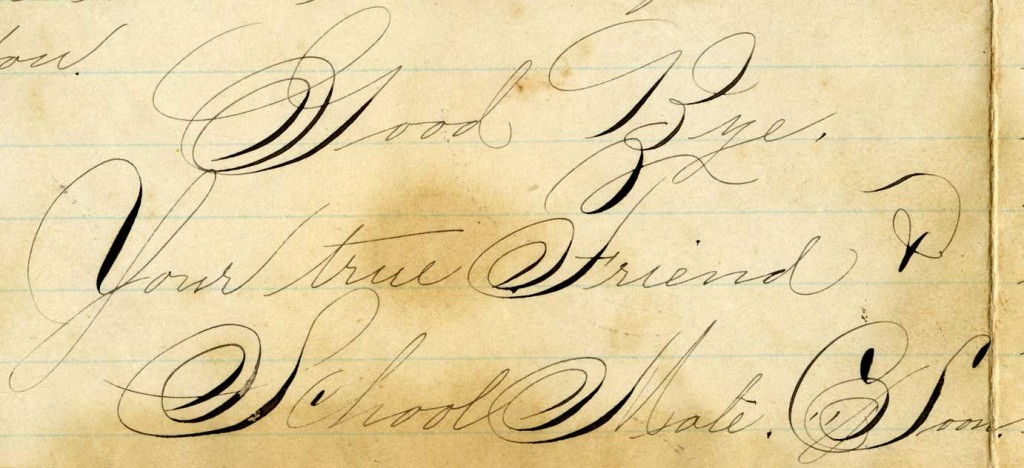

After nearly eight years in the United States, Charlie finally returned to China, armed with a degree from Vanderbilt, in January 1886. The transition to being part of the Methodist mission in Shanghai was hardly an easy one, however, as he revealed in a June 1886 letter addressed to “My dearest friend.” For one thing, Charlie was homesick, and Shanghai was, in effect, a foreign land to a man who had never been far from his birthplace of Hainan when he had lived in China. He wrote, “I am walking once more in the land that gave me birth, but it is far being from a homelike place to me. I felt more homelike in America than I do in Shanghai.” To make matters worse, Charlie had to rely heavily on English as he learned the unfamiliar dialect spoken in the region.

Charlie also immediately chafed under the stern leadership of Dr. Young J. Allen, whom he nicknamed “the great Mogul.” For example, Charlie was denied permission to visit his parents, whom he had not seen for thirteen years, until 1887, prompting him to show a little of his rebellious side in his letter:

“I am very much displeased with this sort of authority; but I must bear it patiently. If I were to take a rash action the people at home might not fail to understand the nature of the case, and they (my Durham friends especially) might think that I am an unloyal Methodist and a law breaker, so I have kept silent as a mouse. But when the fullness of time has come, I will shake off all the assuming authority of the present Supt. [Superintendent] in spite of all his protestation, assuming authority, and the detestation of the native ministry.”

The last statement points to another problem that would plague Charlie throughout his service, namely racial discrimination within the mission. Despite his collegiate training, Charlie felt he was denied the “privileges and equality which [he was] entitled to,” instead receiving the lower pay and position typical of the second-class status of locally-trained, native Chinese ministers.

Yet Charlie stayed with the mission, experiencing ups and downs his first years with the mission. He was finally able to visit his parents, but was crushed to learn of Annie Southgate’s untimely death back in Durham in 1887. Charlie wrote his condolences to James Southgate from Kunshan (future home of Duke Kunshan University) in February 1887, stating that “Miss Annie was one of my best friends.” Later that year, Charlie married Ni Kwei-tseng, also known as Mamie, with whom he would have six children: Ai-ling, Ching-ling, May-ling, Tse-ven, Tse-liang, and Tse-an.

Charlie finally set off on his own in 1892 after six years of missionary work. Addressing rumors back in North Carolina that he had rejected his faith, Charlie wrote to the Raleigh Christian Advocate:

“My reason for leaving the Mission was it did not give me sufficient to live upon. I could not support myself, wife and children with about fifteen dollars of United States money per month. I hope my friends will understand that my leaving the Mission does not mean the giving up of preaching Christ and him crucified.”

Charlie’s initial forays into private enterprise were closely connected with his faith. He started a publishing business, Mei-hua shu-kuan, printing bibles and religious tracts for the American Bible Society. The family’s fortunes increased with further business ventures, such as managing a flour mill and importing manufacturing equipment. Charlie soon began taking an interest in politics. After meeting Sun Yat-sen in 1894, he remained a longtime friend and political supporter of the revolutionary and future leader.

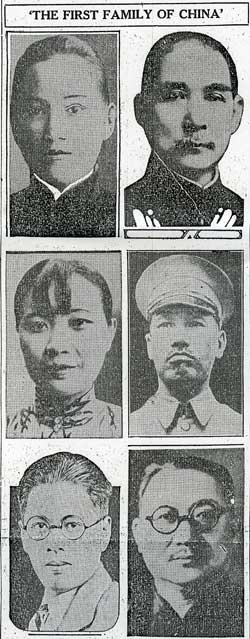

Charlie did quite well financially over time, making enough money to send all six of his children to school in the United States. The education the Soong children received, along with the family’s growing connections in China, put them on the path to creating powerful political and financial dynasty for the first half of the twentieth century. After spending some time as secretary to Sun Yat-sen, Ai-ling married H. H. Kung, a powerful businessman who would later become China’s finance minister. Ching-ling married Sun Yat-sen and wielded considerable political influence during her lifetime. May-ling, a graduate of Wellesley, married Chiang Kai-shek and became a determined and charismatic advocate for the cause of Republican China in the United States. Tse-ven used his Harvard economics degree to great success in the business sector, served as the head of the Central Bank of China, and also acted as China’s finance minister from 1928 to 1933.

Charlie passed away in 1918, before he could fully see the astronomical rise of his family. If he had lived a bit longer, he would also have witnessed a revival of interest in his own life story in the United States, prompted by publicity tours by May-ling, a.k.a. “Madame Chiang Kai-shek,” in the 1930s and 1940s. At Duke University, Soong will never be forgotten as the intrepid young student who helped open up the institution to a wider, more diverse world.

Additional Resources:

- “Charles Soong” by University Archivist Emeritus William E. King. Reprinted from Duke Dialogue, January 30, 1998

- Charles Jones Soong Reference Collection, 1882-1995 (view this collection guide)

- Charles Jones Soong Papers, 1884-1887 (view the collection guide)

Post contributed by Mary Mellon, William E. King Intern for the Duke University Archives. Read her earlier article on Charlie Soong’s Trinity College experience.