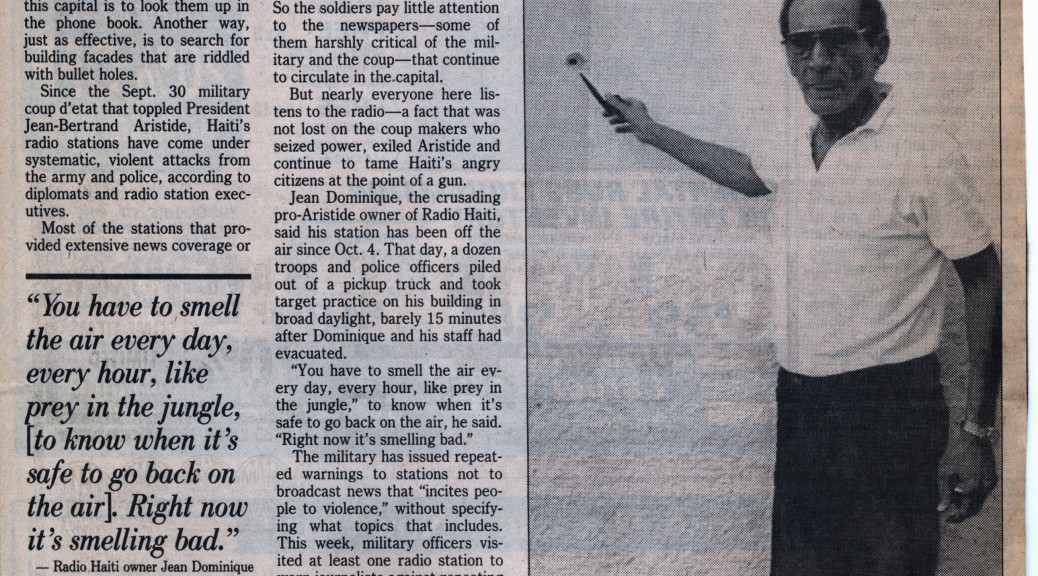

“Why all this noise and all this furor for a man two years dead? Why all these mobilizations throughout the country?” With these words, Michèle Montas began her April 2002 editorial on the second anniversary of the assassination of her husband, Radio Haiti-Inter director Jean Dominique, and station employee Jean-Claude Louissaint. “Why Jean Dominique? This question has been asked for several weeks, in the background of the mobilizations around the second anniversary of the assassination of the journalist Jean Dominique. It is asked in whispers, but the admiring or, for some, incredulous sotto voce at times grows annoyed and strident among those who do not understand that this dead man refuses to die. That a murder perpetrated two years ago, now, continues to make news. Why Jean Dominique?”

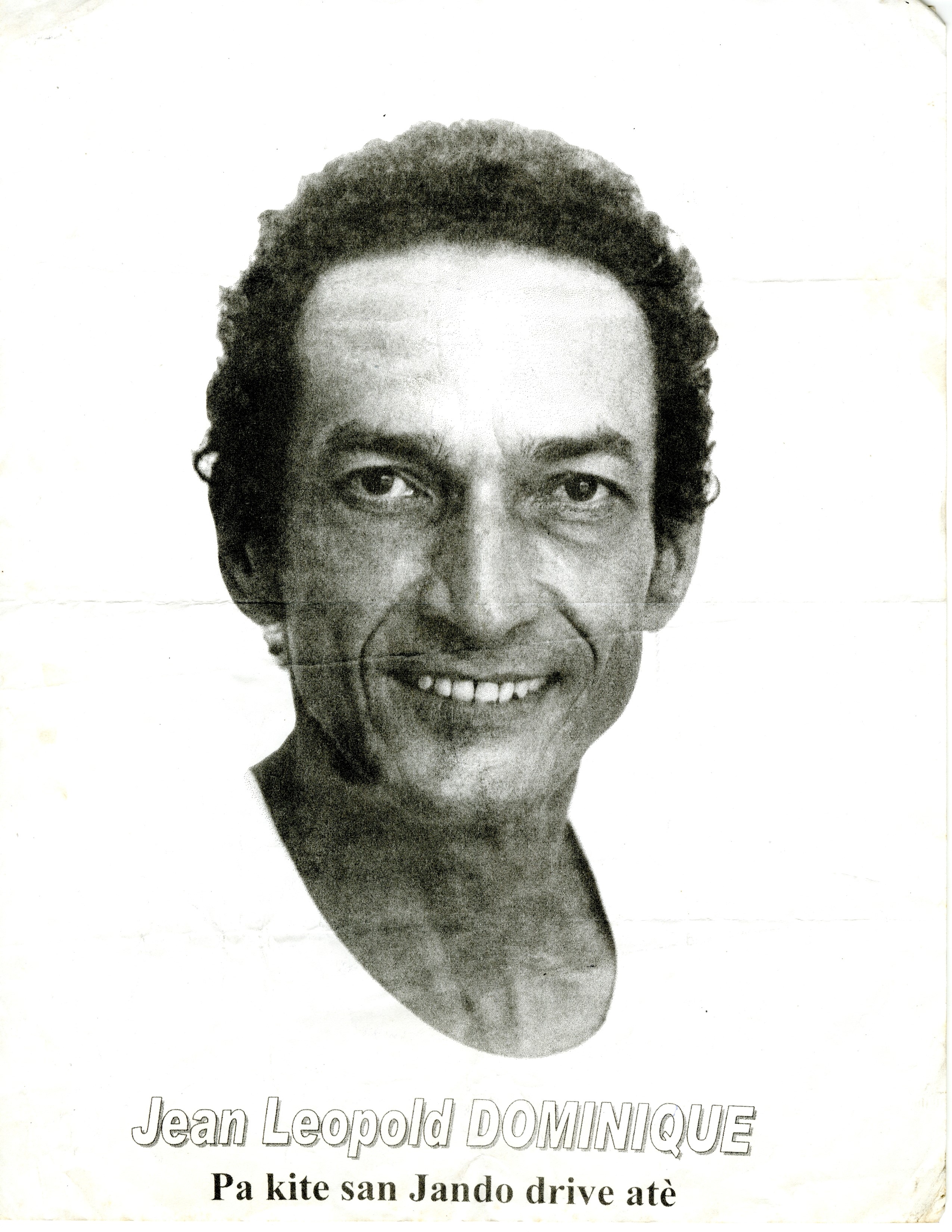

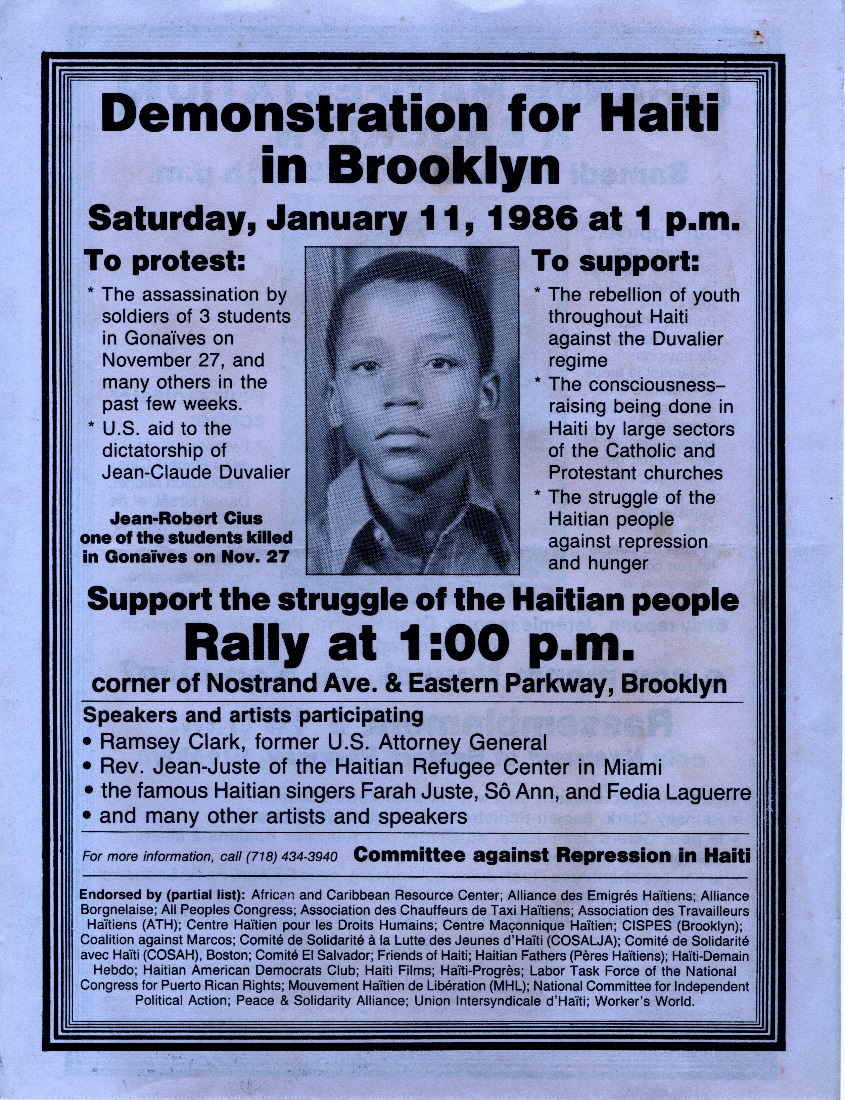

On April 3, 2002, the grassroots human rights group Fondation 30 Septembre poured red paint before the gate of the Ministry of Justice (which leader Lovinsky Pierre-Antoine referred to sardonically as the “Ministry of Injustice”) and displayed an effigy of the slain journalist. The slogan was “Pa kite san Jando drive atè.” “Don’t let Jean Do’s blood pool on the ground.” Two years after the murders, people were angry and frustrated that the judicial process had stalled. Now, sixteen years on, Jean Dominique and Jean-Claude Louissaint have still not found justice. The Jean Dominique case, like so many attempts to combat injustice in Haiti, has been filled with absurdity, a tragicomedy of errors and malfeasance.

Pessimism is seductive in the face of such impunity, when the system is stacked and cynical, when the victories are relative or Pyrrhic, when convicted murderers, torturers, and war criminals like Luc Désir and the perpetrators of the Raboteau massacre eventually walk free. When the state cannot or will not provide justice — when the state provides, instead, a mockery of justice –justice can manifest beyond the courts, beyond the government, beyond the system. It can manifest in the streets. La justice du peuple est en marche.

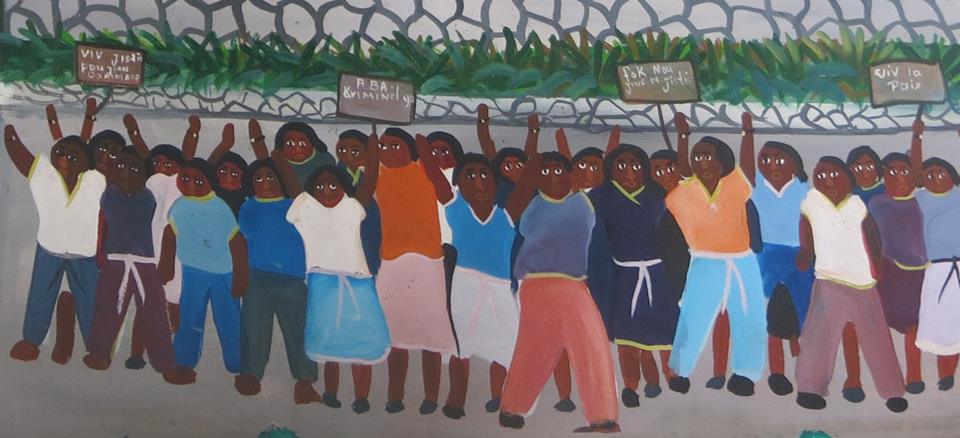

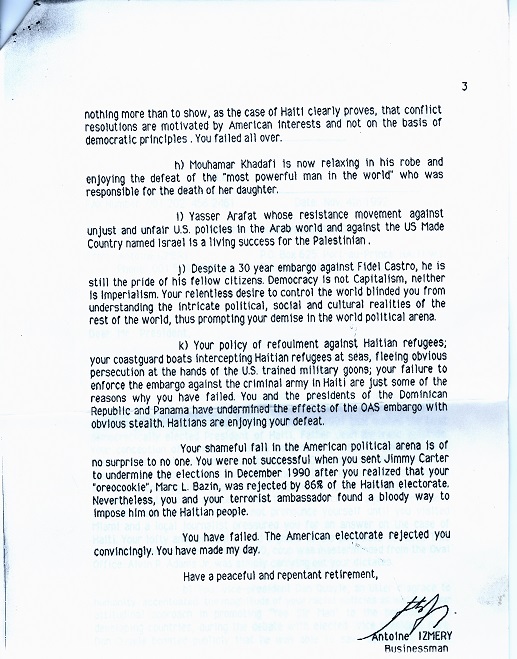

In 2001, artist Maxan Jean-Louis painted the assassination of Jean Dominique and Jean-Claude Louissaint. The canvas is dominated by the Radio Haiti building with its emblematic red-and-blue vèvè (a vodou symbol reimagined in the shape of a microphone). In the background are two men struck down in the parking lot. Jean’s silenced microphone lies beside him. Jean’s family and the Radio Haiti staff weep while the police and the media look on – rather helplessly, it seems, their arms at their sides. Tears run down the face of one of the policemen.

The most dynamic part of the painting are the protestors in the foreground, the men and women standing in the street, outside the station’s walls, clamoring for justice while the weeping policeman looks on. Their arms raised in protest, their lips parted as they shout, they carry signs: DOWN WITH CRIMINALS. WE MUST HAVE JUSTICE. DOWN WITH THE DEATH MACHINE. LONG LIVE PEACE. JUSTICE FOR JOURNALISTS. JUSTICE FOR JEAN DOMINIQUE. Above them is written: APRIL 3 2000. FAREWELL JEAN DOMINIQUE. THE PEASANTS WILL NEVER FORGET YOU.

In the literal sense, that was not how it happened. Jean Dominique was shot just after 6 am, at the time of the daily Creole news broadcast, and he was pronounced dead at l’Hôpital de la Communauté Haïtienne shortly after. There was no time for crowds to assemble while his body still lay on the ground.

The painting is a metaphor, then, or perhaps a depiction of time compressed. The urban and rural masses and civil society organizations did mobilize that very day and for years after: grassroots human rights groups, grassroots peasants’ groups, women’s groups, unions, and ordinary citizens. As Michèle Montas explains, “the mobilizations began on April 3, 2000, through the protests and the expressions of solidarity of hundreds of people shocked by the assassination of a pro-democracy activist who had survived all the regimes against which he had courageously fought, to fall victim to a contract killing during a democratic season that he worked to establish.”

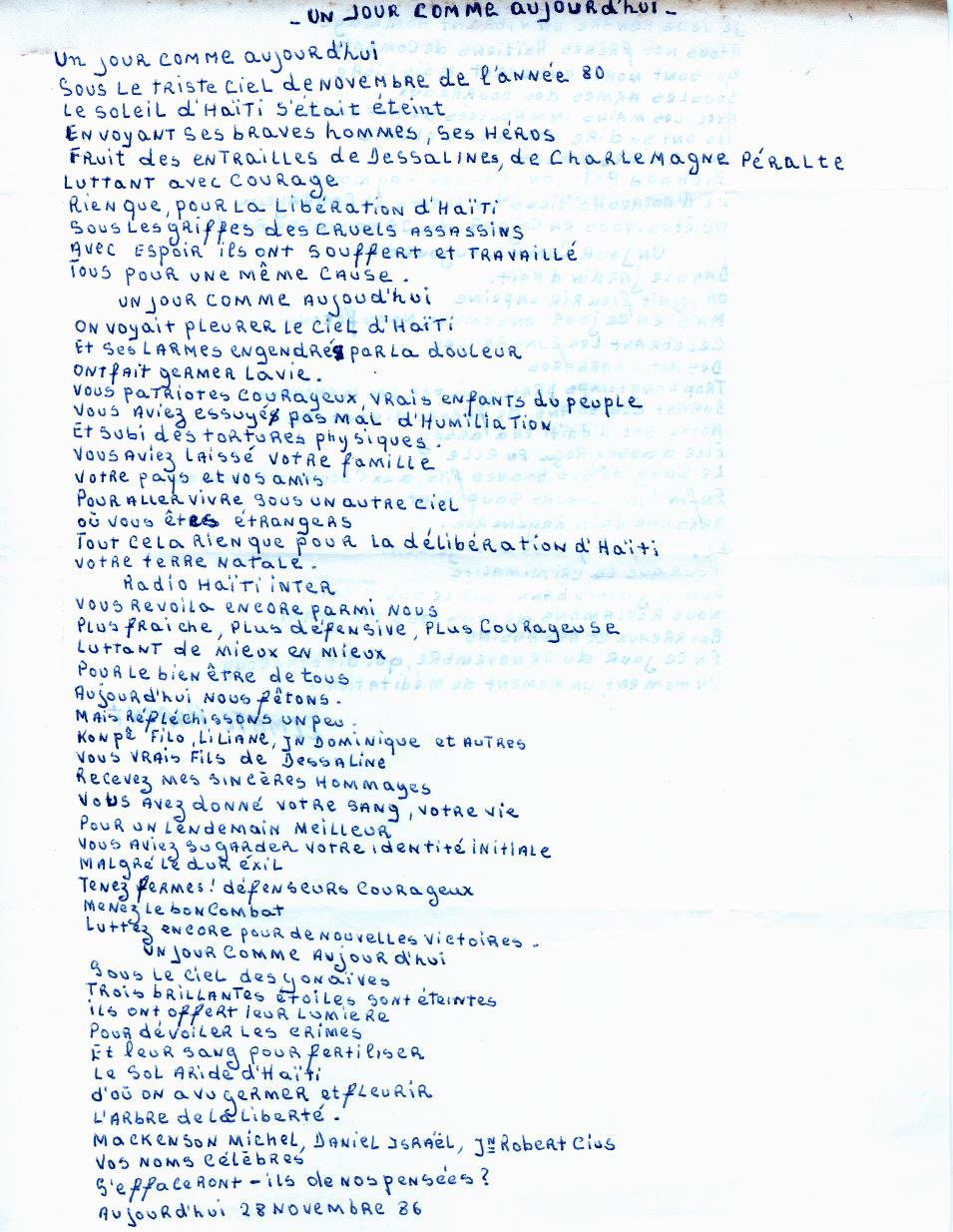

Five days after the murders, on April 8, the state funeral for Jean Dominique and Jean-Claude Louissaint at Stade Sylvio Cator in downtown Port-au-Prince was attended by 15,000 people, of whom 10,000 were rural farmers. On July 31, 2000 – what would have been Jean Dominique’s seventieth birthday – more than 10,000 peasant farmers from the Association des Planteurs et Distillateurs de Léogâne et Gressier gathered at the Darbonne sugar factory to thank and demand justice for Jean Dominique. That same day, the Centre de Production Agricole Jean L. Dominique, run by small-scale coffee growers, was inaugurated in Marmelade. Hundreds of peasant farmers gathered to pay tribute. And that same day, musicians, poets, and vodouisants gathered in the courtyard of Radio Haiti to pay homage to Jean Dominique.

In the archive of things Radio Haiti held onto, I came across a song called “Won’t Jean Dominique Find Justice?” by Haiti Rap Force. From the hand-drawn cover, I assume it was a local rap group from one of Port-au-Prince’s quartiers populaires. They sing that justice is not achieved through only formal, state-sponsored institutions.

Dosye Jean Dominique pa koute sèlman tribinal

sa konsène tout tout moun an jeneral

n’ap bat poun fè ti pèp la bliye

Nou pa gen dwa janm bliye lanmò Jean Dominique

Refren:

Men se ki lès ki gen flanbo-a kap klere chimen-an poun pa tonbe

Men se ki lès ki konn chimen-an ki va di nou kote nou prale

The Jean Dominique case won’t just be heard in the tribunal

It concerns every single person in general

Trying to make the people forget

But we shall not ever forget the death of Jean Dominique

Refrain:

But who will hold the torch that will light the way so we do not fall?

But who knows the path, who will tell us where we are going?

At the end of the editorial, Michèle returns to the question with which she opened. “Why Jean Dominique? Why all this noise, all this noise and all this furor, for a man two years dead? Why these mobilizations reaching well beyond our borders? This question is asked in different tones: with admiration among those who understand only now that justice and the defense of freedom are not a gift, and that they can only be the result of permanent pressure to force institutions and political leaders to act in accordance with their mandates; with hostility on the part of the enemies of the journalist, those who ordered his killing, or those who rejoiced at April 3, 2000, at being freed from a voice so strong and, for certain interests, so troublesome. ‘Jean Dominique pa pitimi san gadò’ [Jean Dominique is not unguarded and free for the taking], as we say in one of our radio spots. His killers had no idea how true that was.”

Thinking about grassroots mobilization in response to injustice reminds me of Jacques Roumain’s Masters of the Dew (Gouverneurs de la rosée). It is the story of Manuel, a poor cultivator from rural Haiti who becomes politically engaged and organizes his fellow peasants to overcome the things that divide them, to unite in defense of their rights and their land. Manuel organizes a konbit, the traditional form of communal labor, before he is stabbed to death. Jean Dominique and his elder sister, the writer Madeleine Paillère, were so moved by novel that they translated the dialogue into Haitian Creole and adapted it for radio in 1972-1973. It is one fitting epitaph for an agronomist-activist, an intellectual who at great cost threw in his lot with the dispossessed, a man who believed that redemption lay not in suffering, but in solidarity.

On chante le deuil, c’est la coutume, avec les cantiques des morts, mais lui, Manuel, a choisi un cantique pour les vivants: le chant du coumbite, le chant de la terre, de l’eau, des plantes, de l’amitié entre habitants, parce qu’il a voulu, je comprends maintenant, que sa mort soit pour vous le recommencement de la vie.

It is the custom to mourn by singing hymns for the dead, but he, Manuel, had chosen a hymn for the living – the song of the konbit, the song of the soil, of the water, of the plants, of friendship between peasants, because he wanted, I understand now, that his death be for all of you the a new beginning of life.

Post contributed by Laura Wagner, PhD, Radio Haiti Project Archivist.

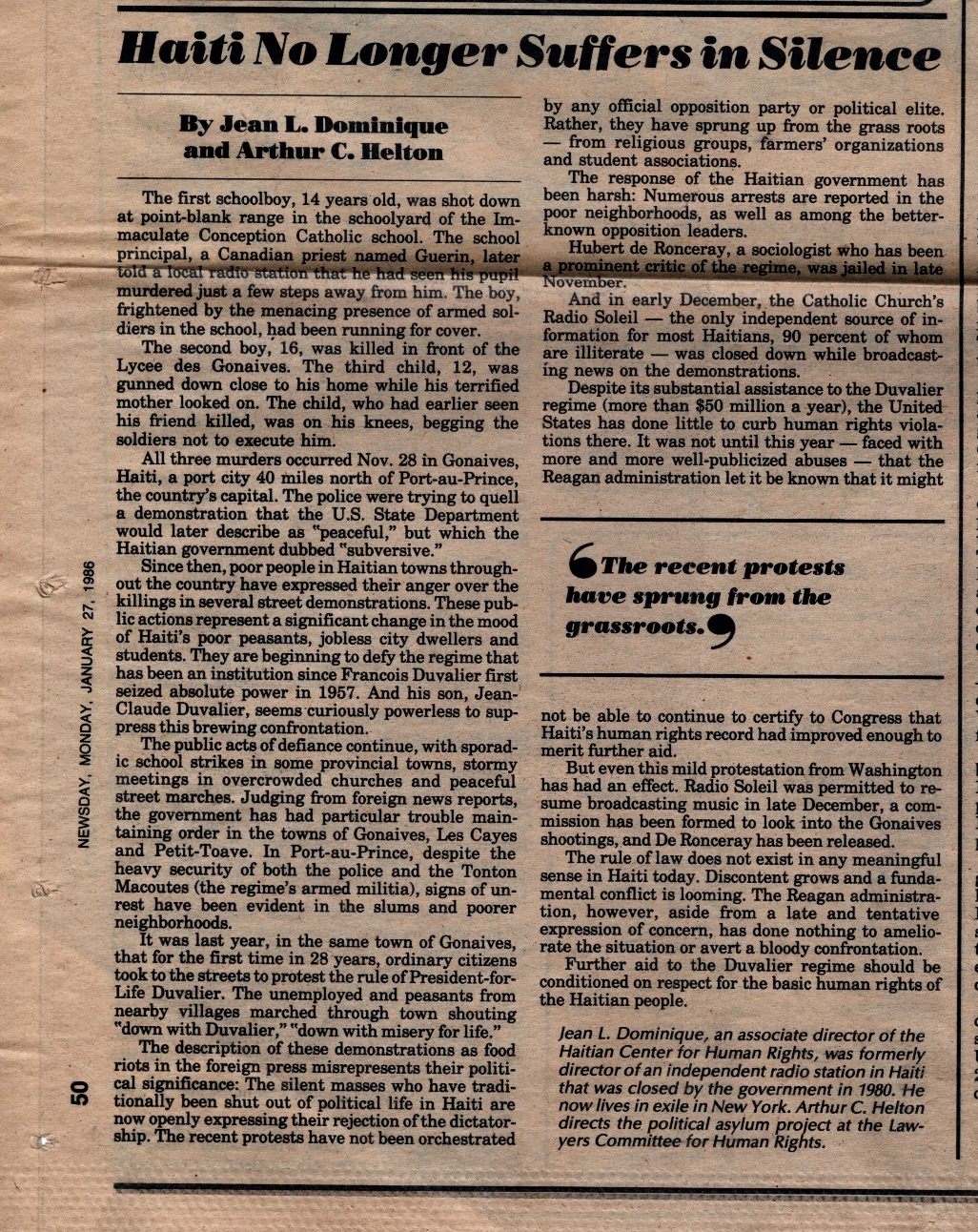

The Voices of Change project was made possible through a generous grant from the National Endowment of the Humanities.