This post is contributed by Erin Rutherford, Josiah Charles Trent Intern, History of Medicine Collections

Morganton, NC: Spake Pharmacy

Item hbirdw0001

Warren Bird Collection Artifacts

History of Medicine artifacts collection, 1550-1980s

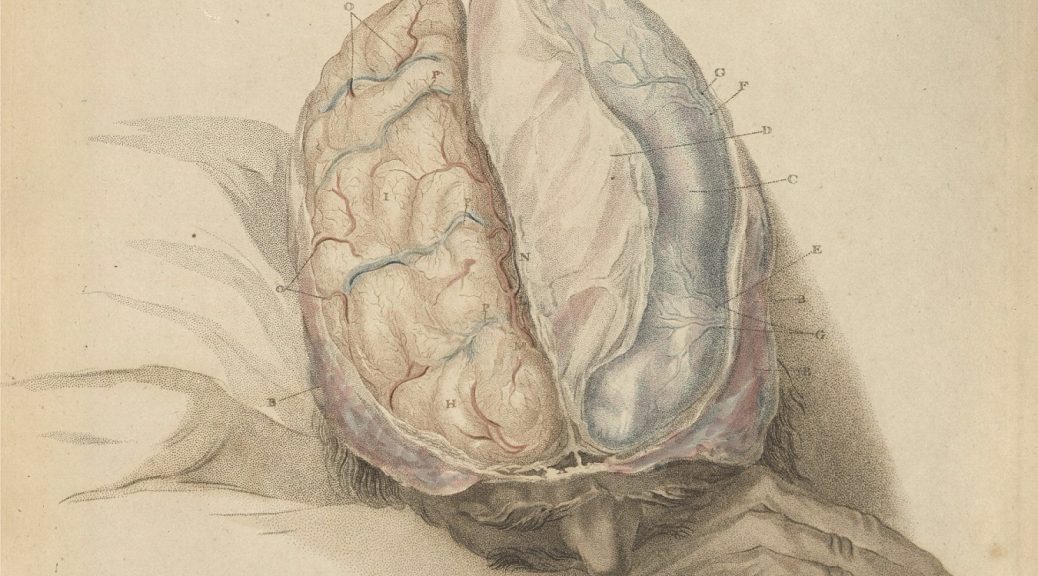

There are many extraordinary items in the History of Medicine artifacts collection: Bloodletting fleams, trepanation kits, bone saws, and ivory handled dental tools. But for me, the most magic dwells in the unassuming items that ask us to tell their stories, such as a diminutive paper cylinder measuring 3 ¼ inches in height and 2 inches in diameter. This Kraft brown tube is capped on each side by scalloped-edge paper in dark blue. I fall in love with the simplicity and utility of this object – its design, its size, its weight in my hands. A small amount of its contents, Purified Talcum Powder, remains inside. A label emblazoned across the front declares that the product was dispensed at Spake Pharmacy in Morganton, North Carolina.

The January 1937 edition of The Carolina Journal of Pharmacy heralds the opening of the Mimosa City’s newest drug store: “The Spake Pharmacy is the name of a new drug store which was formally opened in Morganton on Dec. 9 (1936) by Mr. Y. E. Spake. The new proprietor has spent fourteen years in drug work in Morganton, coming to that town from Kings Mountain where he was a partner in the wholesale drug firm of the Mauney Drug Co. The prescriptionist will be Mr. W. P. Phillips, originally from Morehead City, who goes to Morganton from Charlotte where he was connected with J. P. Stowe and Co. The new store, Mr. Spake says, ‘will offer complete prescription service, in addition to maintaining a modern fountain and a complete line of other medical supplies, cosmetics, and other goods.’”[1] At the time of the store’s opening, purified talcum powder could be obtained from a wholesale druggist for approximately 20 to 40 cents per pound.

Freeman Perfume Co., Cincinnati. Text on reverse explains difference between talcum and face powders. Offer for a sample of Freeman’s Face Powder. For sale by G.E.B. Fairbanks Druggist, Providence, R.I.

Cosmetics Trade Samples and Sachet collection, 1890s-1930s

Box 1

Item RL11349-0024

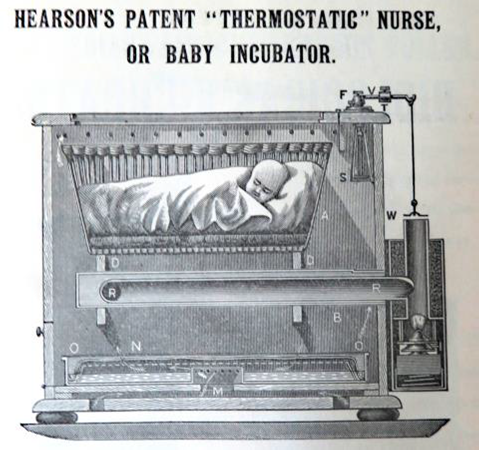

Talcum powder is a refined powder form of the mineral talc, which rose to commercial popularity during the 19th and 20th centuries. Advertised as ‘thoroughly antiseptic’ and intended for use by the young and old alike, it was generally applied after bathing, shaving, or partaking in outdoor activities. Talcum powder was thought to cool the skin on hot days, sooth irritation, and keep the skin ‘comfortable.’ On babies, it was used to prevent chafing and ‘nappy’ soreness. Adults dusted the powder on their bodies to absorb dampness and neutralize body odors. Advertisements aimed specifically at women promoted its scented quality, proclaiming that talcum powder would keep them ‘dainty’ and fragrant ‘like a newly opened flower’ when essential oils were added to the product – typically rose, lavender or violet. Given its myriad uses, powder-filled tin canisters, glass bottles, and paper cylinders like the one dispensed at Spake Pharmacy, would have been a common sight within the medicine cabinets and on the dressing tables of many American households.

Occupying a small space on North Sterling Street, Spake Pharmacy first operated under the catchphrase, “The little store with the big heart.” In addition to dispensing and delivering prescriptions, they sold fountain drinks, Blue Ridge Ice Cream, and Martha Washington candies. In the early 1940s, Yates Ellis Spake moved his business to a prominent location at the corner Union and Sterling Streets and adopted the iconic slogan, “On the Square.” While the talcum powder cylinder is undated, the presence of this simple slogan on the label indicates that it was dispensed sometime after the move.

Between 1936 and January of 1953, Spake and his team filled over 300,000 prescriptions.[2] A set of these were captured in a small 1950s feature, entitled ‘Rx Oddity’: “Yates E. Spake of Morganton sends us a list of three prescriptions filled for a customer recently: (1) 1 bottle of Cortone Tablets, $30; (2) 1 Rx for Terramycin Caps., $14.40; and (3) 1 Rx for an ice cream cone, 5c. ‘I have never experienced anything like this during all my years in the drug business,’ says Yates.”[3]

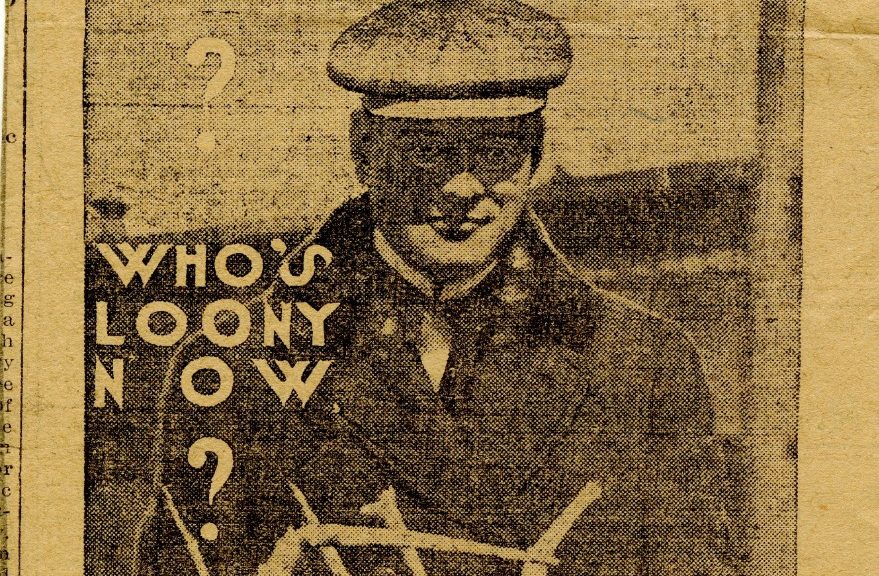

Y.E. Spake appears as the first standing from left.

Under the leadership of J.A. Hurt, Spake Pharmacy moved locations for a third and final time in 1966 to 307 West Union Street. Spake Pharmacy last appears in the Carolina Journal of Pharmacy’s ‘List of Drug Stores’ for Morganton in 1970 with J. A. Hurt, Jr. certified as pharmacist in charge. By 1971, the address was assumed by Burke Pharmacy, Inc.

[1]Happenings of Interest. (January 1937). The Carolina Journal of Pharmacy, Vol. XVIII(1), 8.Named Manager of Spake Pharmacy. (March 1953). The Carolina Journal of Pharmacy, Vol. XXXIV(3), 94.

[2]Named Manager of Spake Pharmacy. (March 1953). The Carolina Journal of Pharmacy, Vol. XXXIV(3), 94

[3]Rx Oddity. (December 1951). The Carolina Journal of Pharmacy, Vol. XXXII(12), 581.

Please join the

Please join the