Post contributed by Steph Crowell, Trent Intern for the History of Medicine Collections.

In the spirit of the season, and in preparation for Screamfest VI here at the Rubenstein, we’ve been combing through our collections for all things creepy and unsettling. The History of Medicine has plenty of these things to go around, from medical instruments and artifacts to anatomical flap books to scary stories submitted to Duke’s old parapsychology lab (which includes the original material for the movie Poltergeist!), and much more. Being so spoiled for choice, we thought it best to ease into the festivities with some small, humble, yet significant contributors to the history of medicine: insects.

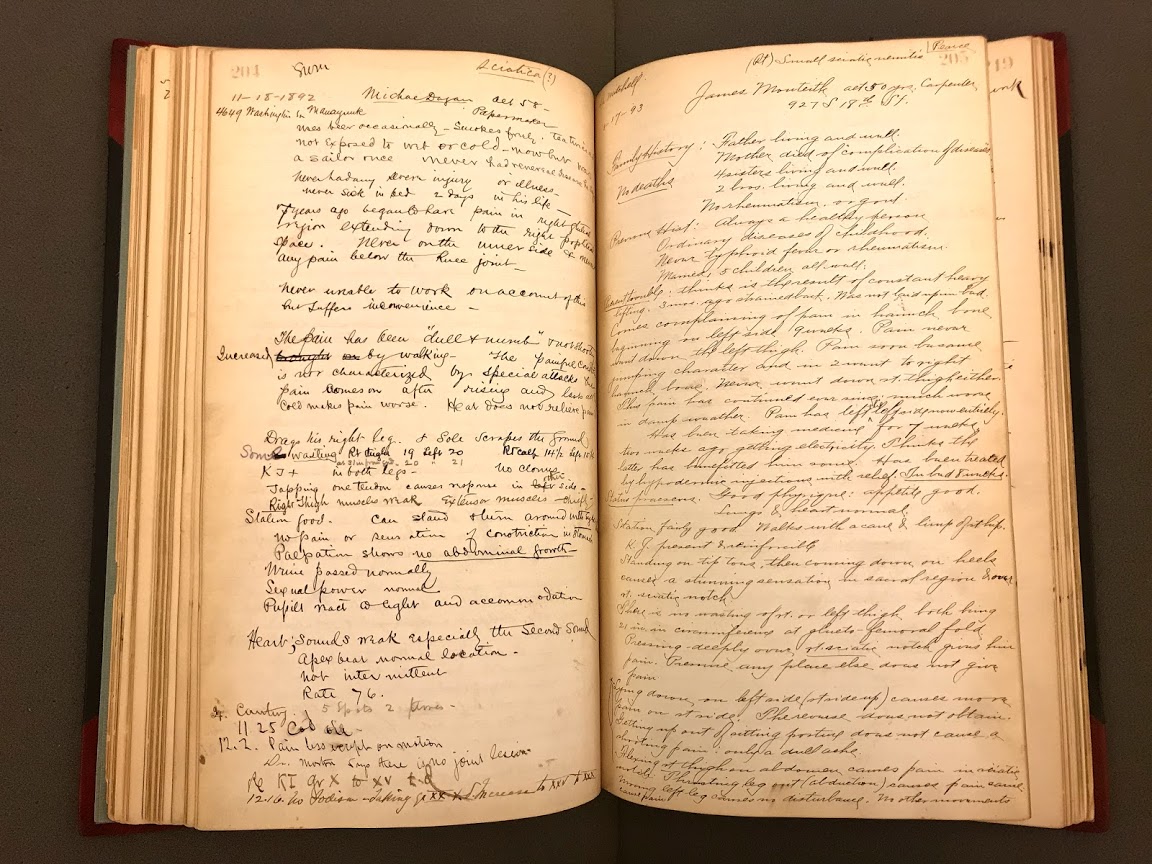

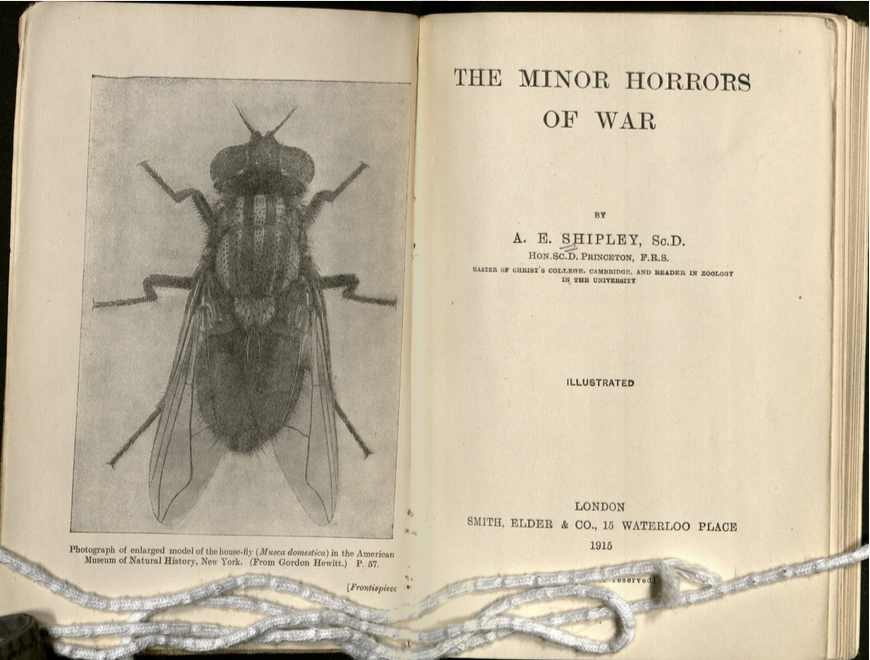

One might expect something called The Minor Horrors of War to contain stories related to the horrors of battle, the horrors of field medicine, or something equally gruesome, but this little volume takes a different direction: it talks about the how different arthropods and annelids may cause and treat illnesses for soldiers in the field. It covers lice, bedbugs, flies, mites, moths, and, leeches.

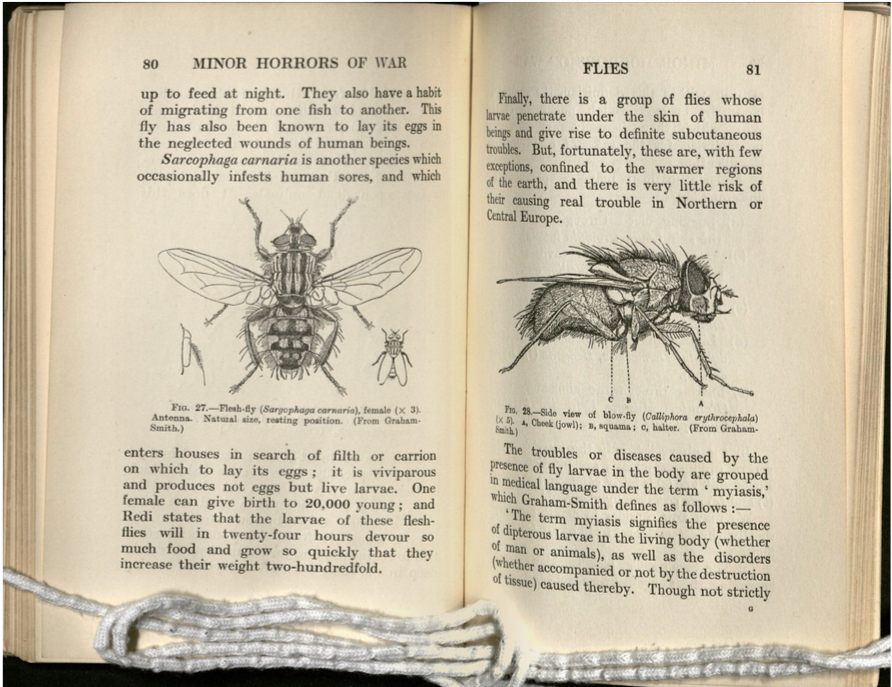

The wonderful thing about this book is the author’s ability to break up the technical entomological information he provides with easy-to-understand and frequently witty prose. For example, in the flies section of the book there is a particularly gruesome section on the impact of the Congo-floor-maggot, blow-flies, and others responsible for myiasis (“the presence of… larvae in the living body… as well as the disorders… caused thereby.” pp. 81). He ends this section a kind of silver lining to the discussion and says that we have “at least discovered the reason why Beelzebub was called the ‘Lord of the Flies’” (86).

Throughout the book, as you can probably tell by the images so far, are figures depicting many of the creatures being discussed. Throughout, you can see all these different kinds of creatures in varying degrees of magnification depending on the needs of the author. As shown below with a couple pictures of mites, this magnification can range from birds-eye views of different phases of an insect’s development to an incredible zoom-in that can more clearly show the reader each individual extremity and wrinkly that may be found on the insect’s body.

Finally, onto leeching. Leeching is perhaps one of the most famous uses of invertebrates in medicine (you can read a little about why that is the case here), and leeches are the creature that this author spends the most time describing. Unfortunately, you won’t find many images of a leeching session in progress but, just like in the rest of the book, there are many illustrations on the fine details of the leech itself. Despite the author’s claim that leeches are “undoubtedly degenerate earth worms” (124), he spends a great deal of time describing both medicinal leeches and exotic leeches (pictured below).

If you have some time, particularly this month, we would highly recommend stopping by for a little while and taking a look at this book. You can find the catalog record here. It’s as easy as hitting the green request button on the page- just remember to give us a couple of days’ notice of your visit so we can be sure we have time to get it ready for you.

Don’t forget to keep an eye out for news and announcements related to Screamfest VI. It’s on the 30th this year, so be sure to leave some room in your schedule to come take a break with us! If you have any questions, as always feel free to drop by or contact us any time.

Suggested readings:

The insect folk– a more pleasant depiction of various kinds of insects. Dating back to 1903, this book was created to appeal to children and depicts friendlier versions of friendlier insects, such as dragonflies and crickets.

A natural history of the most remarkable quadrupeds– Like the previous book, this is more of juvenile-friendly account of certain creatures. It extends beyond insects to cover other animals like birds, reptiles, and more.

A short discourse concerning pestilential contagion– this could be a drier bit of reading, but if you’re interested in how insects who spread disease such as the plague were dealt with in the public health sphere, this could be a book for you.