Post contributed by Laura Wagner, P.h.D., Radio Haiti Archivist

This blog post is in French and Haitian Creole as well as English. Scroll down for other languages.

Cet article de blog est écrit en français et créole haïtien en plus de l’anglais. Défilez l’écran vers le bas pour les autres langues.

Blog sa a ekri an franse ak kreyòl anplis ke angle. Desann paj la pou jwenn lòt lang yo.

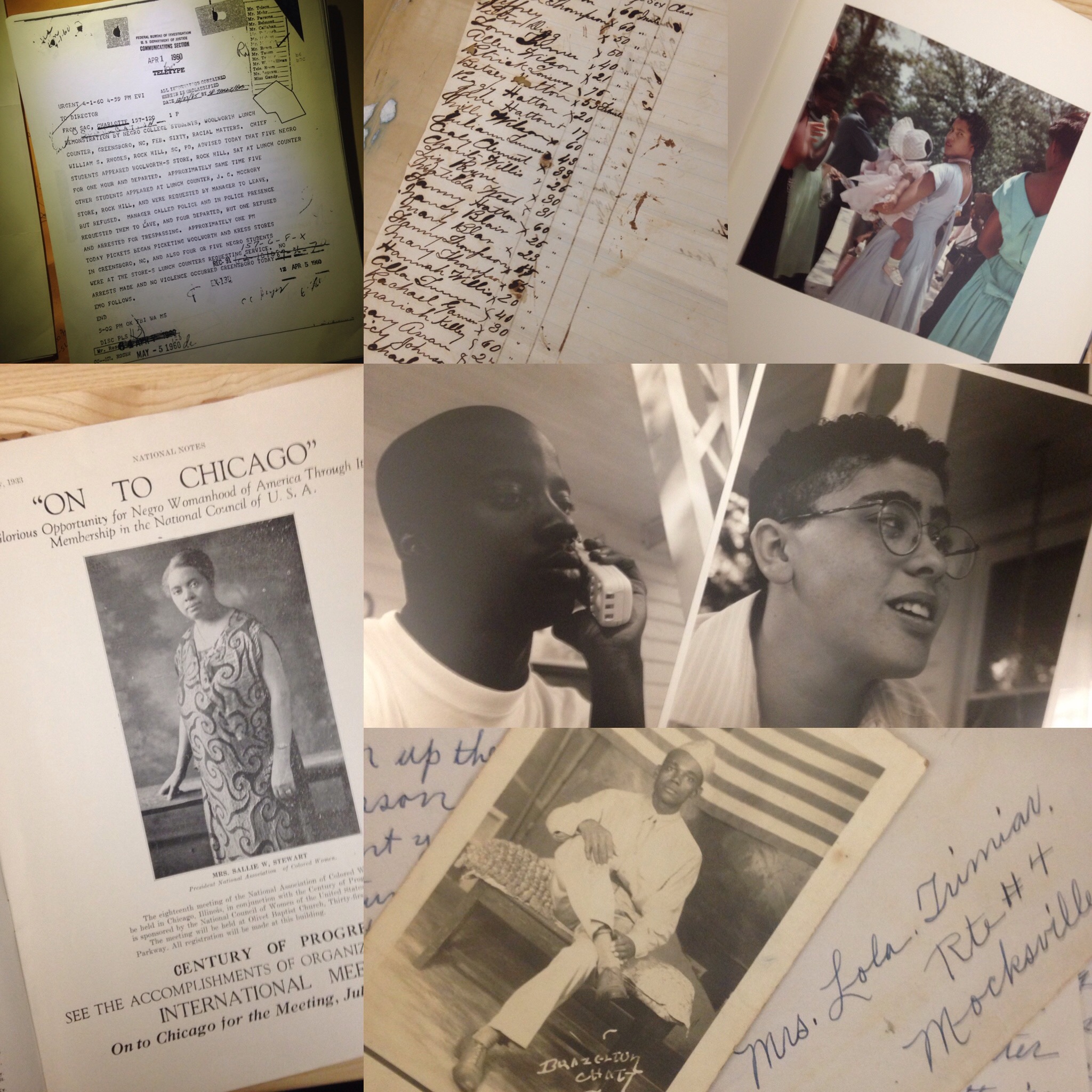

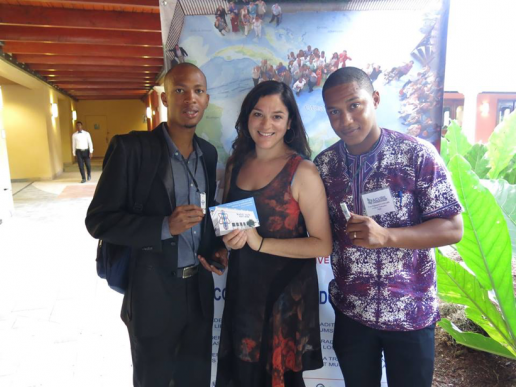

Assistantes-étudiantes Krystelle Rocourt et Tanya Thomas avec Laura Wagner.

Asistan-etidyan Krystelle Rocourt ak Tanya Thomas ansanm avèk Laura Wagner.

The David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library is thrilled to announce the successful completion of the first major stage of Radio Haiti: Voices of Change, made possible through the generous support of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

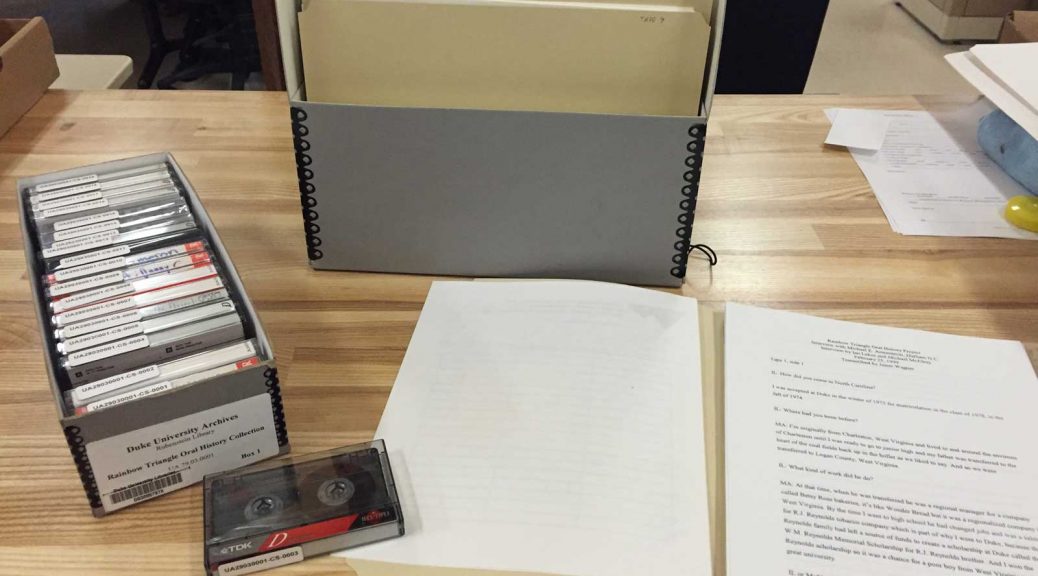

Between July 2015 and spring 2018, project archivist Laura Wagner, audiovisual archivist Craig Breaden, and a committed team of student assistants have:

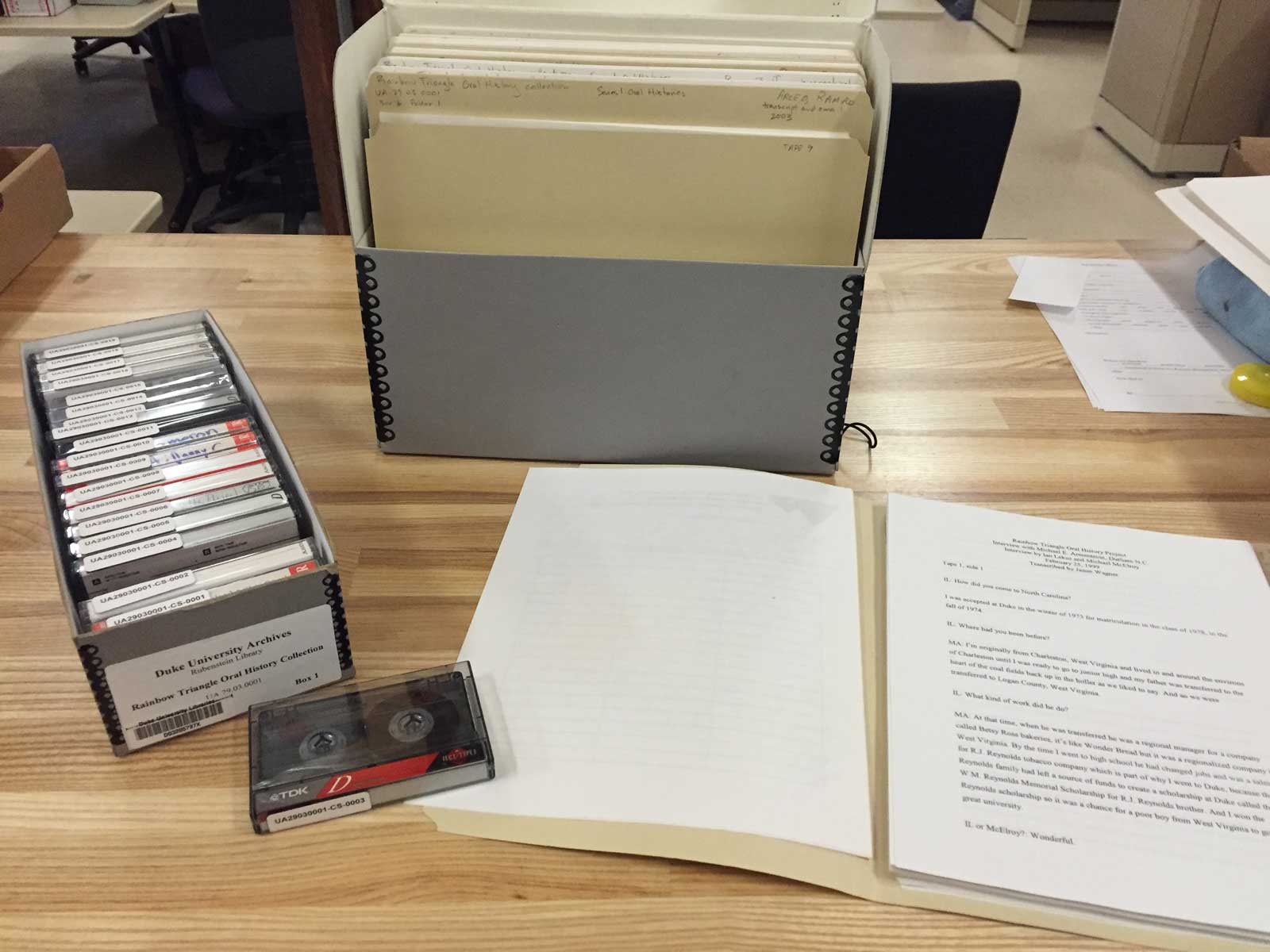

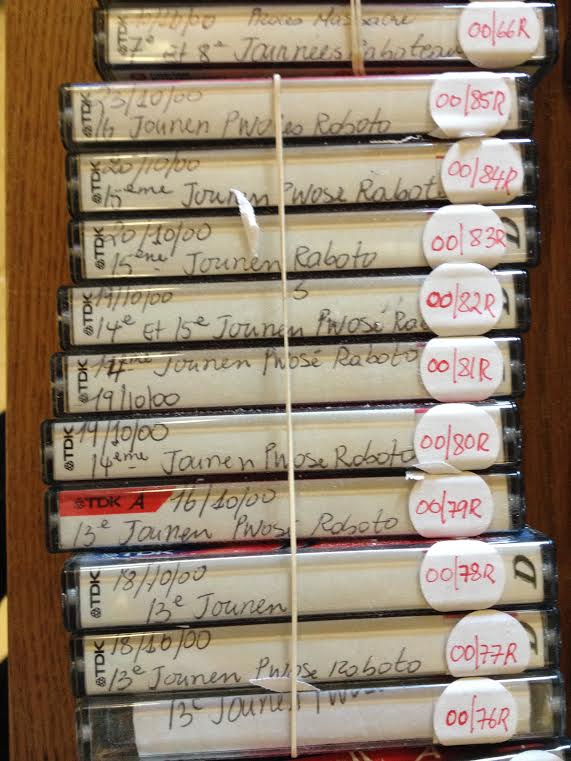

- completed preliminary description of the entire Radio Haiti audio collection, including nearly 4,000 open reel and cassette audio tapes

- managed the cleaning and high-resolution digital preservation of the tapes at Cutting Corporation in Maryland, and secured a CLIR Recordings at Risk grant to digitize — at Northeast Document Conservation Center — recordings that had suffered acute deterioration

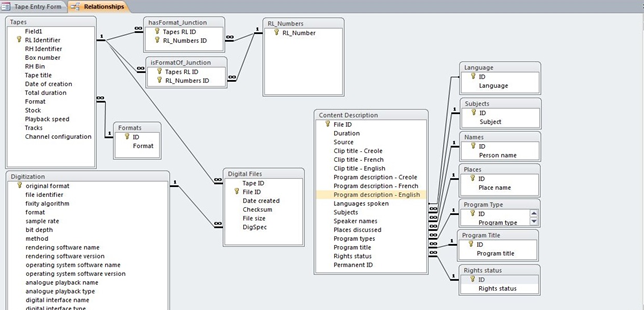

- created additional detailed, trilingual metadata (in Haitian Creole, French, and English) for more than half of the Radio Haiti audio, now available on the Duke Digital Repository

- completed description of the Radio Haiti papers, now available online

Our student assistants and volunteers, past and present, both undergraduate and graduate, have been an invaluable part of this team. They have listened to and described Radio Haiti audio; blogged about the archive; used the materials in the archive in their own research; and brought expertise, excitement, and enthusiasm to this very rewarding but intense project. Mèsi anpil to Tanya Thomas, Krystelle Rocourt, Réyina Sénatus, Catherine Farmer, Eline Roillet, Sandie Blaise, Jennifer Garçon, and Marina Magloire for everything you have done and continue to do.

In addition to our in-house work on the archive, Laura has also conducted two outreach trips to Haiti to raise awareness of the project and to distribute flash drives to cultural institutions, libraries, community radio stations, and grassroots groups.

But the project isn’t over yet! We are currently seeking additional funding to continue in-depth detailed description of the audio.

Onward!

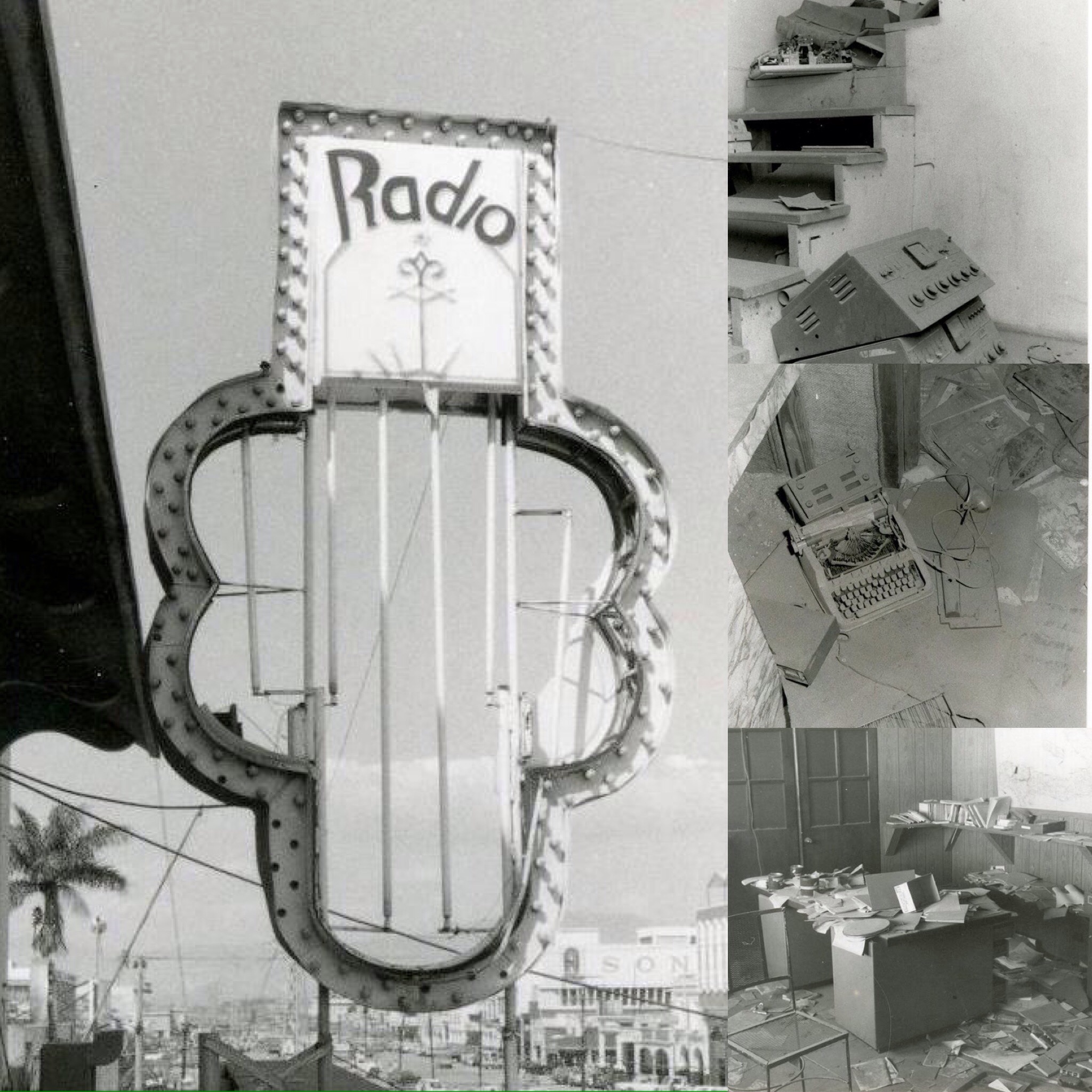

Laura explique comment utiliser les archives de Radio Haïti à des étudiants en agronomie du département de la Grand’Anse (Cap-Rouge, juin 2017).

Laura montre kèk edityan nan agwonomi ki soti nan Grandans koman sèvi avèk achiv Radyo Ayiti yo (Kap Wouj, jen 2017).

La bibliothèque David M. Rubenstein Livres Rares & Manuscrits est fière d’annoncer le succès de la première étape du projet Radio Haiti: Voices of Change, rendu possible grâce au généreux soutien de la National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH). Entre juillet 2015 et mars 2018, Laura Wagner, chef de projet et Craig Breaden, archiviste audiovisuel, appuyés par une équipe d’étudiants passionnés, ont :

- rédigé une description préliminaire de l’intégralité des archives audio de Radio Haïti, dont près de 4000 enregistrements sur bobines et cassettes

- géré le nettoyage, la préservation et la numérisation en HD des cassettes via l’entreprise Cutting Corporation (Maryland) et digitalisé les enregistrements les plus fragiles au Northeast Document Conservation Center grâce à la bourse CLIR Recordings at Risk

- créé des métadonnées trilingues (créole haïtien, français et anglais) détaillant plus de la moitié de la collection, maintenant disponibles sur Duke Digital Repository

- classifié l’ensemble des archives papier de Radio Haïti, maintenant disponibles en ligne

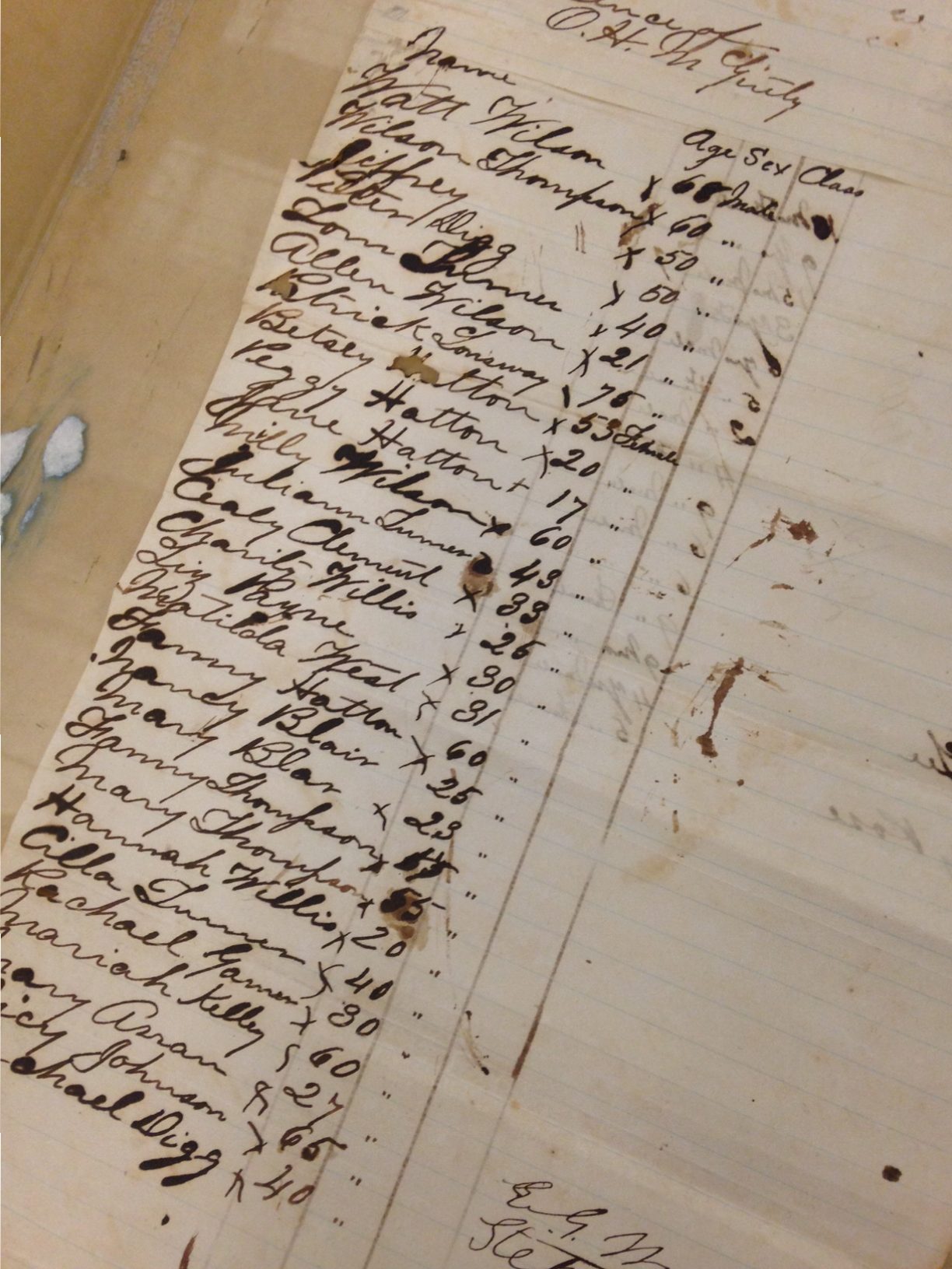

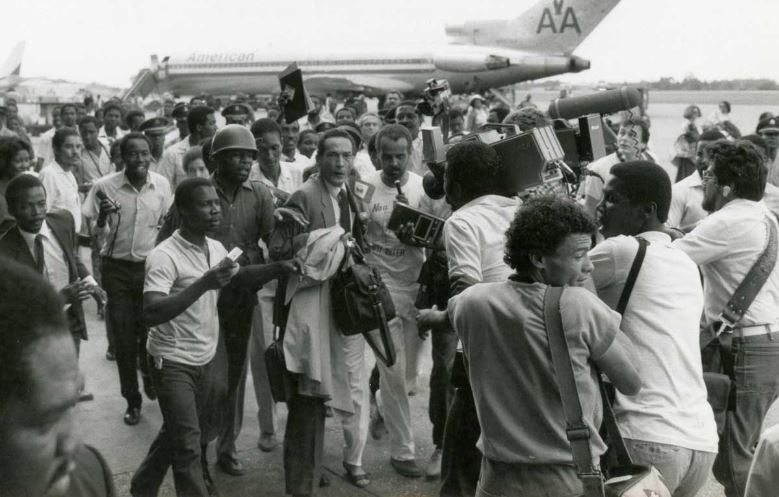

Les partisans de Radio Haïti accueillent Jean Dominique et Michèle Montas à l’aéroport de Port-au-Prince lorsqu’ils sont revenus en Haïti après l’exil, mars 1986.

Fanatik Radyo Ayiti vin akeyi Jean Dominique ak Michèle Montas nan ayewopò Pòtoprens aprè yo tounen lakay yo nan mwa mas 1986.

Nos étudiants et nos volontaires, passés et présents, en licence, master et doctorat ont joué un rôle inestimable au sein de l’équipe. Ils ont écouté et décrit des centaines d’émissions de Radio Haïti, rédigé des articles de blog au sujet de la collection, utilisé les documents pour leurs propres recherches et amené leur expertise, leur enthousiasme et leur motivation à ce projet intense et très gratifiant. Mèsi anpil à Tanya Thomas, Krystelle Rocourt, Réyina Sénatus, Catherine Farmer, Eline Roillet, Sandie Blaise, Jennifer Garçon et Marina Magloire pour vos précieuses contributions.

En plus du travail en interne sur la collection, Laura s’est également rendue en Haïti par deux fois afin de promouvoir le projet et de distribuer des clefs USB contenant les archives à diverses institutions culturelles, bibliothèques, stations radio locales et associations.

Mais le projet n’est pas encore terminé! Nous sommes actuellement à la recherche de financement supplémentaire pour poursuivre la description détaillée en profondeur des documents sonores.

En avant!

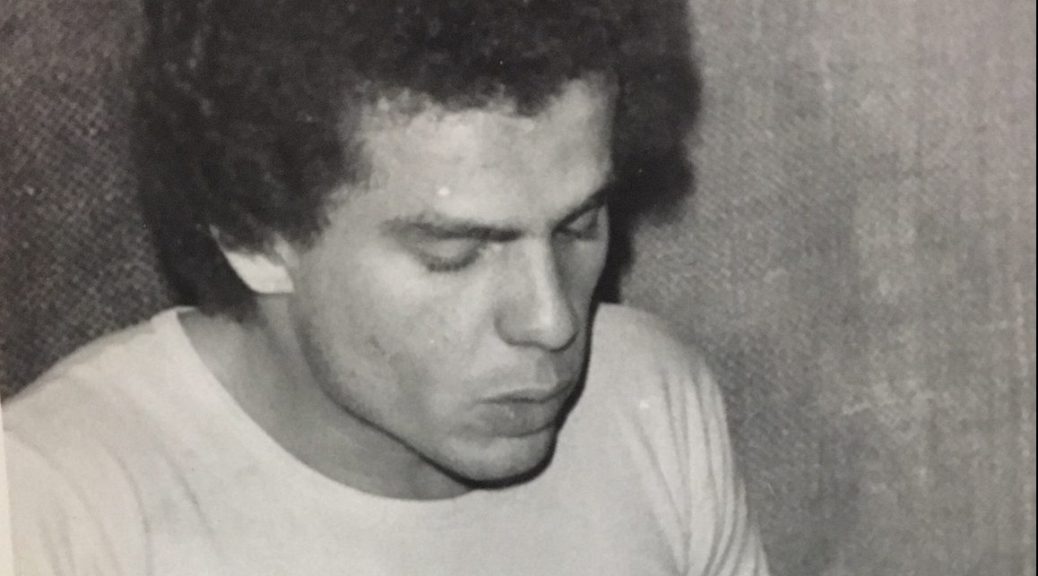

Craig Breaden protège la table de mixage originale de Radio Haïti à l’aide de rembourrage.

Craig Breaden pwoteje pano miksaj orijinal Radyo Ayiti a pou l ka dòmi dous.

David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library (Bibliyotèk David. M. Rubenstein pou Liv ak Maniskri ki Ra) gen anpil kè kontan anonse ke premye etap pwojè Radio Haiti: Voices of Change (Radyo Ayiti: Vwa Chanjman) a abouti. Pwojè sa a te posib gras a finansman jenere National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) la.

Soti nan mwa jiyè 2015 rive nan prentan 2018, achivis prensipal la Laura Wagner, achivis odyovizyèl la Craig Breaden, ak yon ekip etidyan trè angaje gentan reyalize objektif swivan yo:

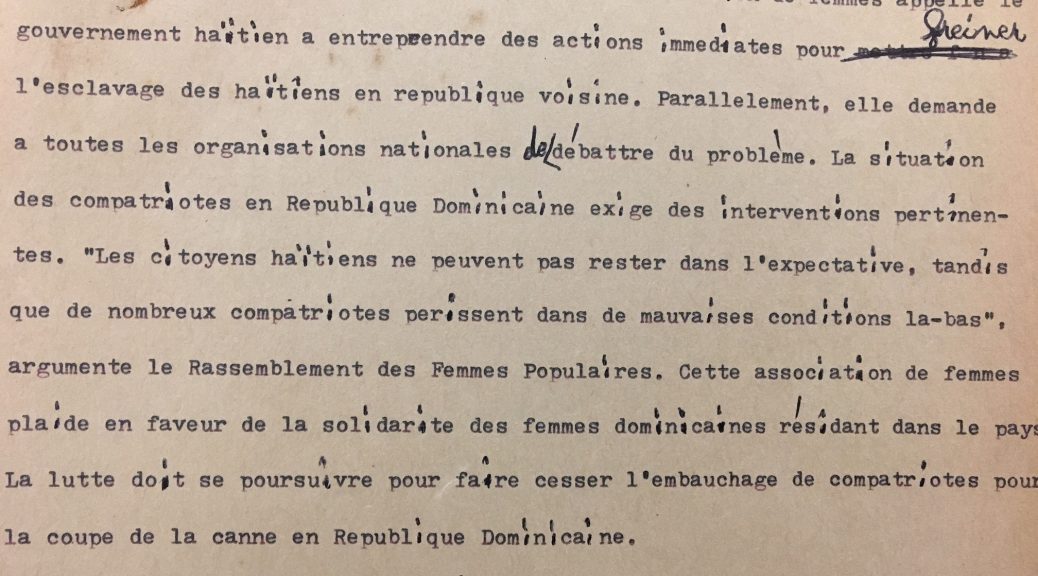

Une bande magnétique de Radio Haïti, avant et après le néttoyage et la conservation.

Bann mayetik Radyo Ayiti avan ak aprè li fin netwaye epi konsève.

- Yo fin fè yon premye deskripsyon sou tout dokiman sonò Radyo Ayiti yo, ki gen ladan yo prèske 4.000 bann mayetik ak kasèt

- Yo jere netwayaj ak konsèvasyon dijital tout tep yo, ki te fèt nan Maryland avèk konpayi Cutting Corporation, epi yo jwenn yon sibvansyon CLIR “Recordings at Risk” pou dijitalize tep ki pi frajil epi pi domaje yo nan Northeast Document Conservation Center

- Kreye deskripsyon ki pi detaye epi ki trilèng (an kreyòl, franse, ak angle) pou plis pase 50% dokiman sonò Radyo Ayiti yo, ki disponib kounye a sou Duke Digital Repository la

- Deskripsyon tout achiv papye Radyo Ayiti yo, disponib kounye a sou entènèt

Etidyan ki travay sou pwojè sila a, kit yo asistan peye kit yo benevòl, kit yo etidyan nan lisans, metriz, oswa nan doktora, bay pwojè a yon gwo kout men. Yo tande epi dekri odyo Radyo Ayiti a, ekri blog sou achiv yo, sèvi avèk materyèl yo nan pwòp rechèch pa yo, epi yo pote anpil ekspètiz, eksitans, ak antouzyas pou pwojè sa a, ki se yon pwojè ki vo lapenn men ki difisil, tou. Mèsi anpil Tanya Thomas, Krystelle Rocourt, Réyina Sénatus, Catherine Farmer, Eline Roillet, Sandie Blaise, Jennifer Garçon ak Marina Magloire pou tout sa nou fè pou sovgade eritaj Radyo Ayiti-Entè, ak tout sa n ap kontinye fè.

Anplis ke travay n ap fè lakay nou nan Karolin di Nò, Laura gentan fè de vwayaj ann Ayiti pou sansibilize moun sou pwojè a epi pou distribye djònp bay enstitisyon kiltirèl, bibliyotèk, radyo kominotè, ak òganizasyon de baz.

Men pwojè a poko fini! Aktiyèlman n ap chèche lòt finansman siplemantè pou nou ka kontinye fè deskripsyon detaye dokiman sonò yo, an pwofondè.

Ann ale!

Laura avec Gotson Pierre d’AlterPresse, média haïtien indépendant (Port-au-Prince, février 2018).

Laura avèk Gotson Pierre, responsab AlterPresse, medya endepandan ann Ayiti (Pòtoprens, fevriye 2018).

The processing of the Radio Haiti Archive and the Radio Haiti Archive digital collection were made possible through grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities.