Today, March 24, 2016, marks the fortieth anniversary of the Argentine military coup that ushered in one of the Western Hemisphere’s most repressive regimes. Seeking to quash “subversion” and liberalize the economy, the coalition of military and civilian leaders who seized power in March 1976 instituted a vicious, secretive system of kidnapping, torture, and killing that claimed tens of thousands of lives and damaged countless more.

Each March 24, now deemed the Day of Remembrance for Truth and Justice, Argentina honors these victims and energizes the ongoing struggle for accountability. Yet this year’s commemoration has assumed an unusual character, as President Barack Obama’s ill-timed visit to Argentina has focused the lion’s share of attention on the U.S.’ own role in first encouraging and later opposing the dictatorship. The involvement of the U.S., however, is far from the whole story. Indeed, focusing on this topic alone obscures the pioneering work of the coalition of Argentine human rights groups that fought, at great personal risk, to denounce the dictatorship, demanding justice for its victims and punishment of its crimes.

In this post I turn away from the presidential-visit frenzy to focus instead on one of the less-heralded members of the anti-regime coalition, the Movimiento Judío por los Derechos Humanos (MJDH, or Jewish Movement for Human Rights). Founded in August 1983 by Argentine journalist Herman Schiller and U.S.-born Rabbi Marshall T. Meyer, the MJDH served as a pole of Jewish anti-regime activism. Yet despite its significance, the MJDH has received little attention in Spanish and virtually none in English. Fortunately, though, the Rubenstein Library’s Marshall T. Meyer Papers contain a wealth of documents that shed light on Meyer’s role in the organization and on its broader efforts on behalf of truth and justice in Argentina, enabling this brief and timely overview of its work.

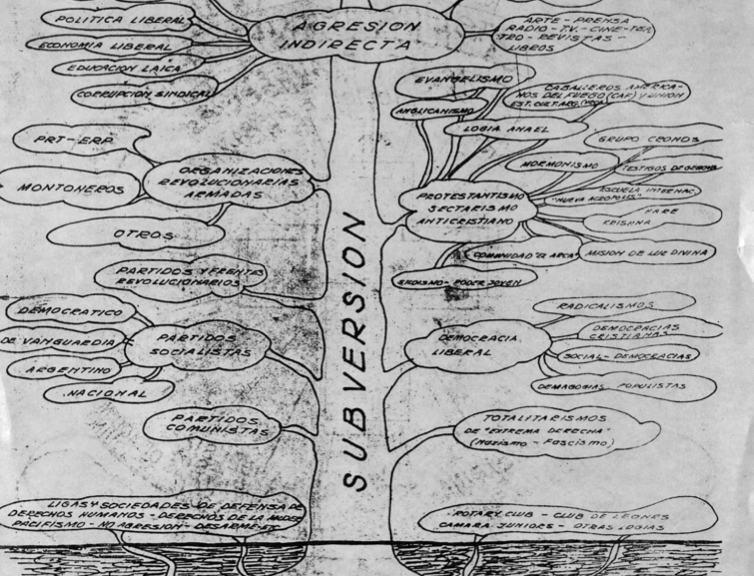

The dictatorship that seized power on March 24, 1976 was a product not only of Cold War anti-communism, but also of Argentina’s long-standing nationalist ideology, an anti-modern vision of the world that combined ultramontane Catholicism and anti-Semitism with a violent desire to quash all opposition. Many within this movement saw Jews a key root of subversion in Argentina and the world at large (powerfully illustrated in the “tree of subversion” illustration below), so it is unsurprising that the country’s large Jewish minority found itself a disproportionate target of state violence. Yet the major institutions of the country’s Jewish establishment—including its umbrella organization, the Delegación de Asociaciones Israelitas Argentinas (DAIA, or Delegation of Argentine Jewish Associations) took a cautious and even cooperative approach to the dictatorship, leaving regime victims and their relatives with few places to turn for support. At the same time, international Jewish organizations like the Anti-Defamation League and the American Jewish Committee fought valiantly to denounce the dictatorship, yet in centering their activism exclusively on the Jewish community, these groups at times divorced the Jewish-Argentine experience of repression from those of other regime victims.

Building on Schiller’s ongoing anti-regime advocacy and Meyer’s longstanding work to support both Jews and non-Jews subject to the dictatorship’s terror, the MJDH came together in mid-1983 in order to advance a holistic vision of social justice that tied the defeat of anti-Semitism to the protection of human rights across all sectors of Argentine society. By this point, the country’s dictatorship was fast approaching the brink of collapse, having been fatally weakened by its humiliating defeat in the 1982 Malvinas/Falklands War with the United Kingdom. It was a moment, Schiller and Meyer understood, when a united opposition reaching across Argentine society could both extract real concessions from the regime and help to shape a most just democratic future.

The MJDH’s first public activity, as described in a November 1984 summary of its first year of organizing, was to convene a Jewish continent to participate in an August 1983 march against the military’s attempt to bestow amnesty upon itself for its many crimes. The success of this act emboldened Meyer and Schiller, encouraging them to plan their first independent rally for October of that year. Amid the political and economic tumult of late 1983, a new wave of anti-Semitism was washing over the country. While DAIA and other community leaders quietly lobbied the dictatorship to combat rising anti-Jewish sentiments, the MJDH took to the streets of downtown Buenos Aires. Despite DAIA’s attempts to derail the event, thousands of supporters gathered at the city’s iconic Obelisk to hear Nobel laureate Adolfo Pérez Esquivel and Hebe de Bonafini, leader of the Mothers of Plaza de Mayo, denounce anti-Semitism and state terror as interlinked assaults on Argentines’ basic human dignity.

The MJDH’s work continued past the free election of civilian President Raúl Alfonsín on October 30, 1983. Throughout the transitional period, Schiller and Meyer organized rallies, speeches, conferences, and teach-ins, working with the Mothers and other human rights advocates to denounce ongoing threats to democracy and to demand the judicial punishment of regime crimes. Together with the efforts of other Argentine human rights groups, these efforts culminated in the precedent-setting 1985 Trial of the Juntas, which sent the dictatorship’s generals and torturers to jail and helped consolidate a new norm of criminal accountability in Argentina and in post-dictatorial societies far beyond. While the MJDH’s activities have diminished in subsequent decades, even today the MJDH continues to push for a full accounting of dictatorship-era abuses and for open discussion of the Jewish community’s complicated role in these difficult years. Spanning these decades of activism is a commitment to the plural vision of Jewish well-being, tied inseparably to universal rights, to which Meyer dedicated his life.

By examining the work of civil society groups like the MJDH, we can help to move beyond decontextualized visions of the dictatorship that present it as a narrow conspiracy, imposed on the country with aid from abroad. The experiences of leaders like Herman Schiller and Marshall Meyer, together with those of the MJDH’s supporters and opponents alike, help us to recover from Argentina’s recent history a measure of the nuance and complexity with which it was lived.

Post contributed by Paul Katz, PhD Candidate in History, Columbia University.

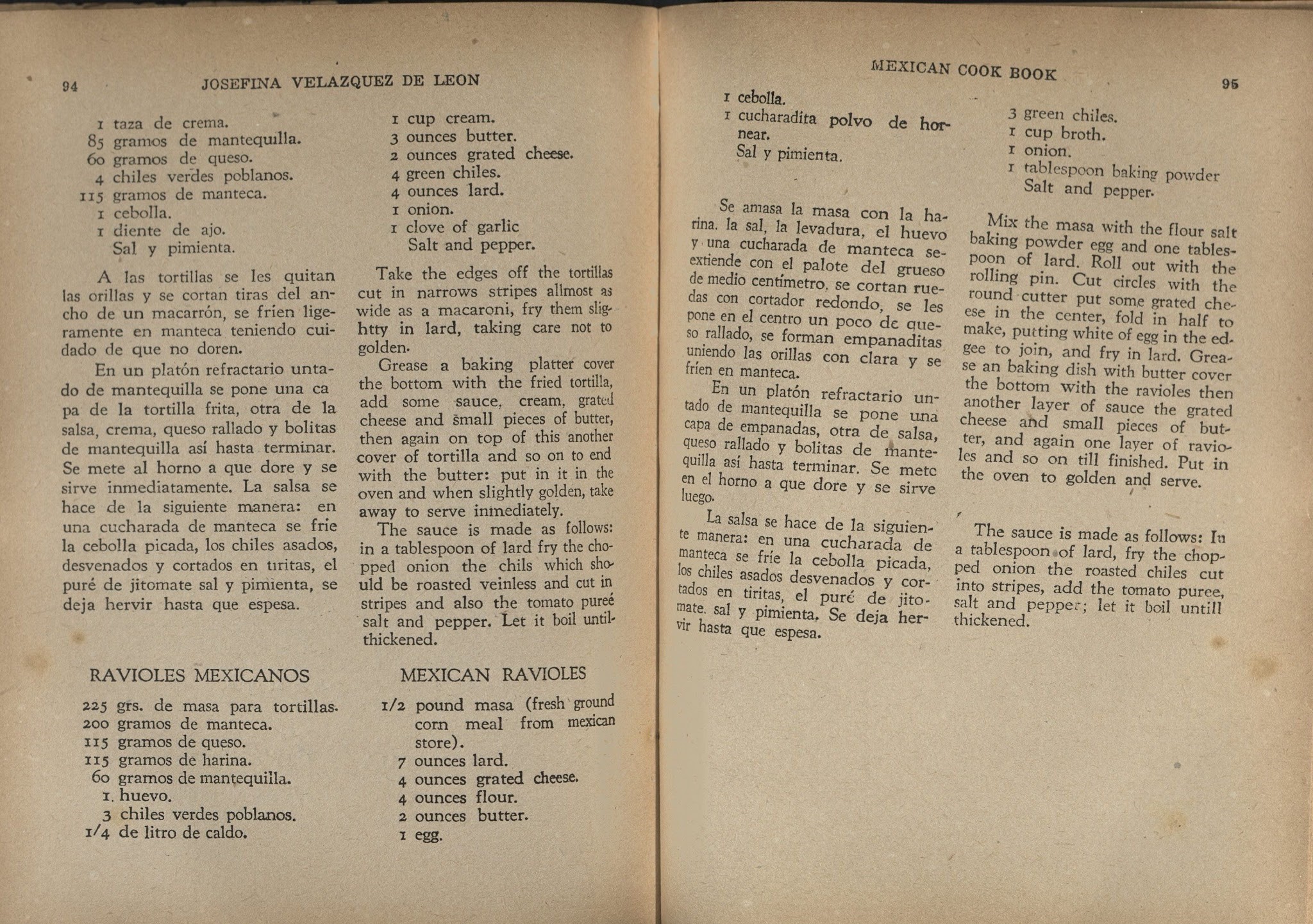

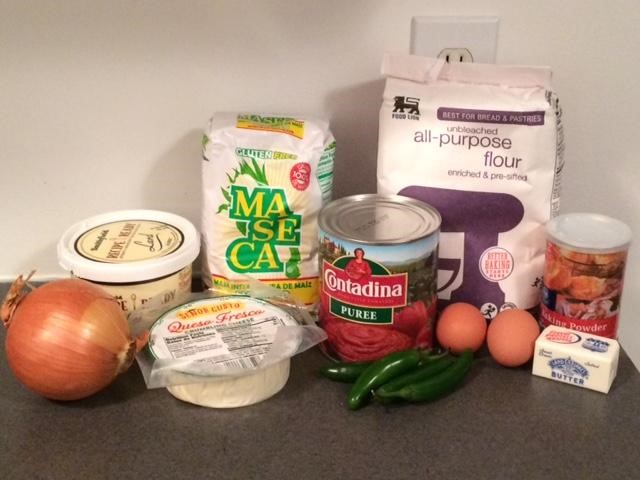

If the E. coli outbreak at Chipotle has you looking for a new way to satisfy your cravings or if you are simply hoping to make a step up from those late night Taco Bell runs, then this post is for you. If you have a hankering for warm cheese and fried foods (and who doesn’t?), Josefina Velazquez de Leon and her

If the E. coli outbreak at Chipotle has you looking for a new way to satisfy your cravings or if you are simply hoping to make a step up from those late night Taco Bell runs, then this post is for you. If you have a hankering for warm cheese and fried foods (and who doesn’t?), Josefina Velazquez de Leon and her

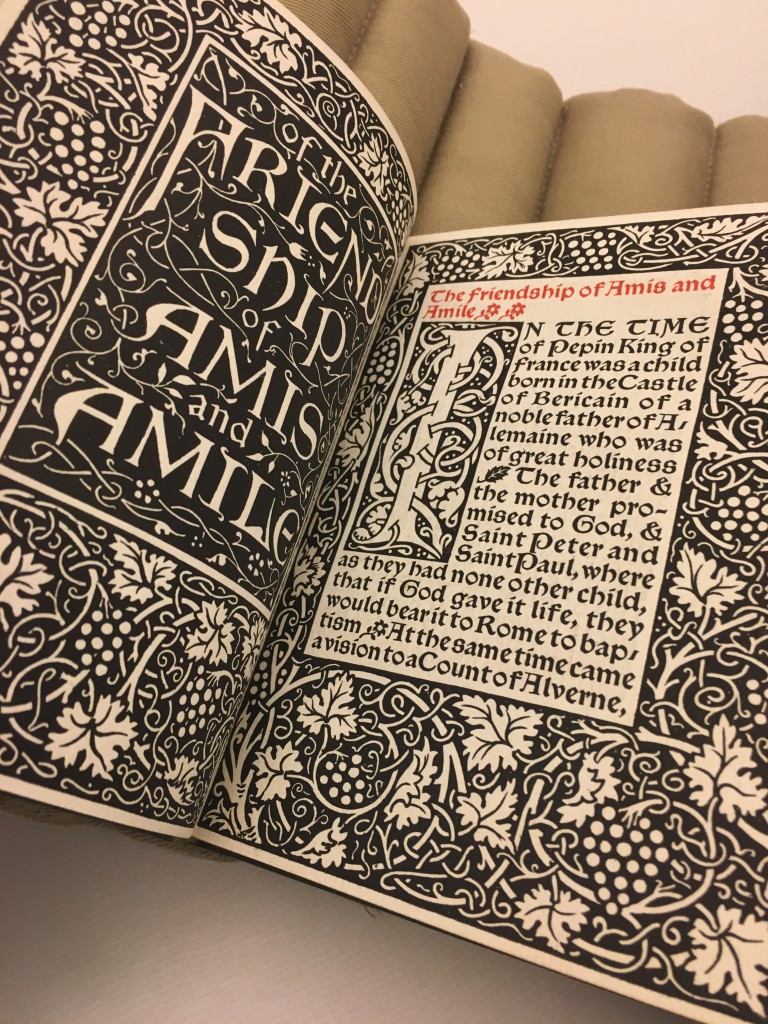

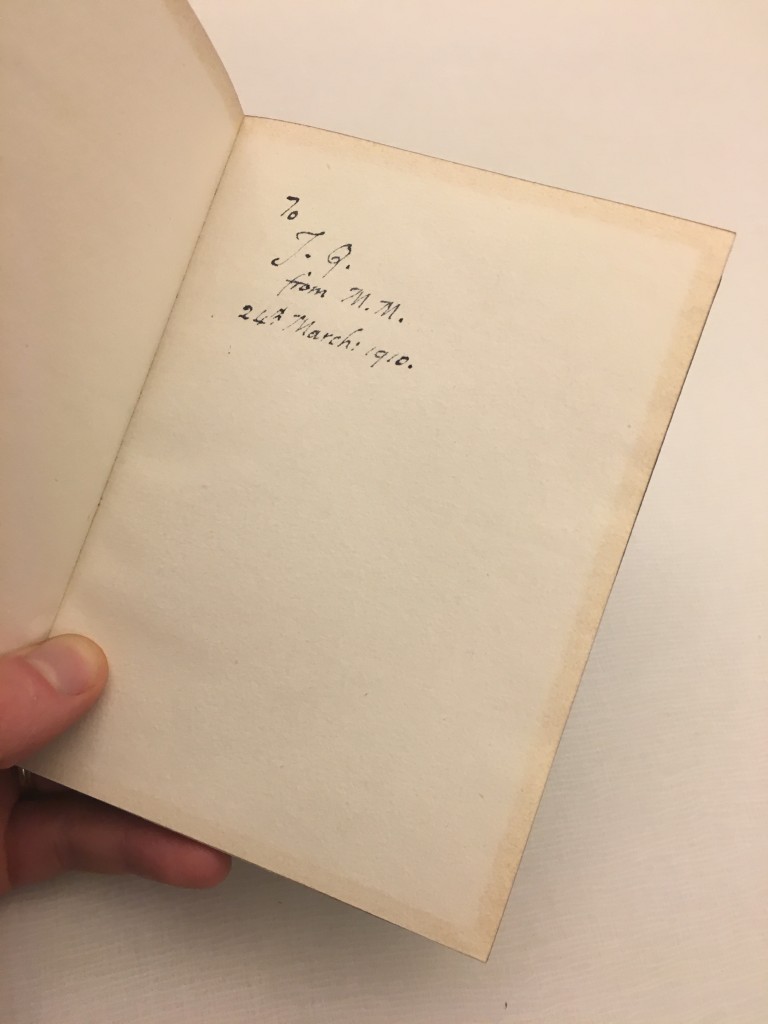

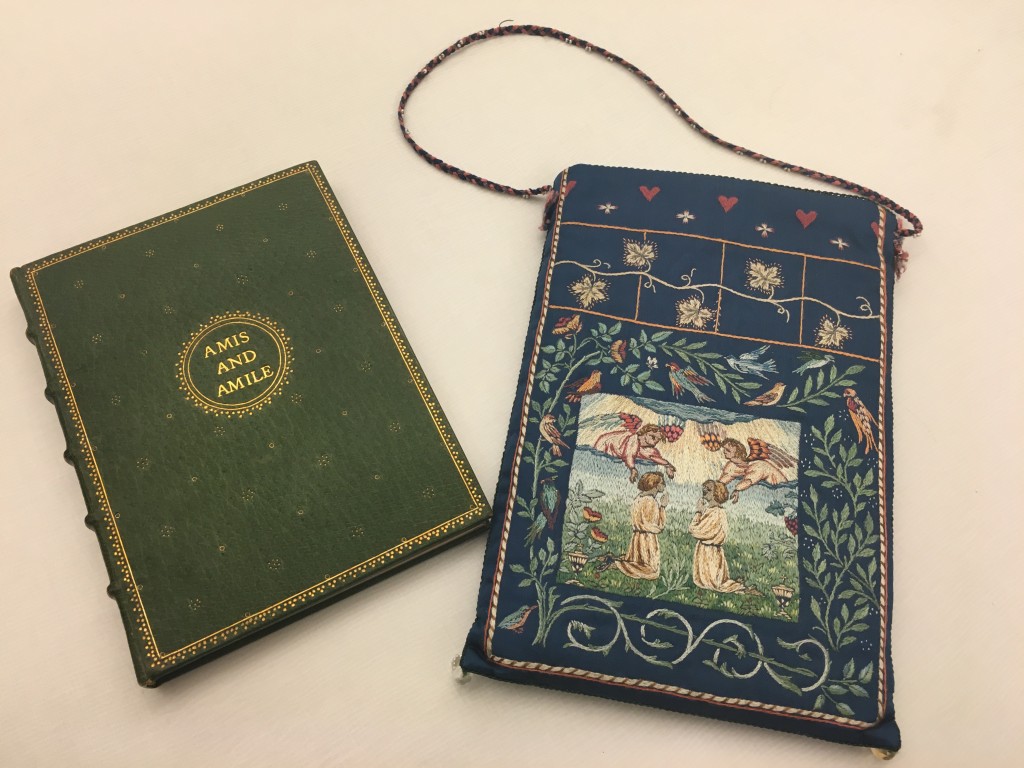

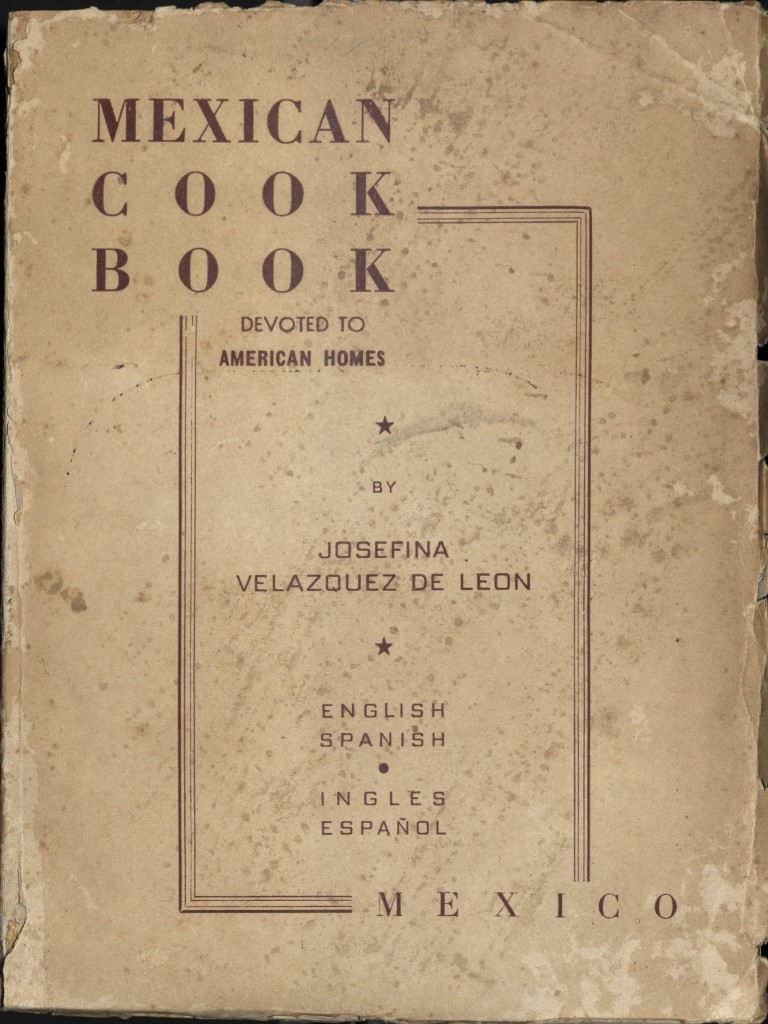

This beautiful copy of

This beautiful copy of