Post contributed by John B. Gartrell, Director, John Hope Franklin Research Center

This summer Duke University Libraries will launch a project to provide expanded digital access to the Behind the Veil: Documenting African-American Life in the Jim Crow South oral history collection, housed in the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Libraries and curated by the John Hope Franklin Research Center for African and African American History & Culture. The project, titled “Documenting African American Life in the Jim Crow South: Digital Access to the Behind the Veil Project Archive,” received a $350,000 Humanities Collections and Reference Resources Implementation grant supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH).

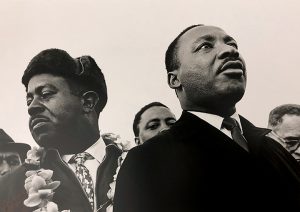

Behind the Veil (BTV) was undertaken by the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University (CDS) from 1992–1995 and co-directed by Drs. William Chafe, CDS co-founder and Alice Mary Baldwin Distinguished Professor Emeritus of History, Robert Korstad, Professor Emeritus of Public Policy, and the late Raymond Gavins, the first African American faculty member in Duke’s Department of History. Chafe, Korstad, and Gavin’s vision for and title of the project refer to the concept of the “veil” introduced by scholar and activist W.E.B. DuBois in his iconic book The Souls of Black Folk (1913). In that work, DuBois discussed the metaphorical concept of the veil as “separating the two worlds of white and black,” designed to protect African Americans who had to balance comporting their lives as subservient and compliant in front of a White dominated society while simultaneously living free in their own community.

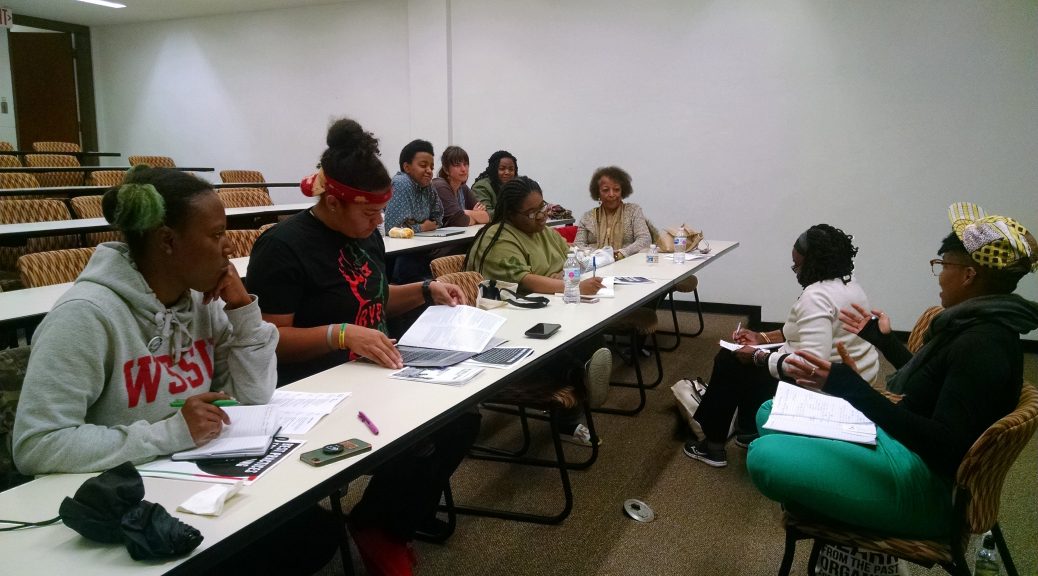

BTV was a groundbreaking documentary project for its time that recorded and preserved the living memory of African American life during the age of segregation in the American South. Over the span of three summers, cohorts of graduate students and early career scholars from universities across the country received training with the project’s scholarly board and then resided in selected locales for two weeks to conduct oral histories. The team conducted interviews with more than one thousand community elders who shared their memories from the Jim Crow Era of legal segregation. Nineteen distinct communities were identified for interviews: Albany, GA; rural Arkansas; Birmingham, AL; Charlotte, NC; Durham, NC; Enfield, NC; New Bern, NC; LeFlore County, NC; Memphis, TN; Muhlenberg, KY; New Iberia, LA; New Orleans, LA; Norfolk, VA; Orangeburg, SC; St. Helena, SC; Summerton, SC; Tallahassee, FL; Tuskegee, AL; and Wilmington, NC.

All of the BTV project files were transferred to the John Hope Franklin Research Center in subsequent years after the project’s completion. The BTV collection encompasses a number of formats including over 1,200 taped audio cassette interviews and 3,000 photographic strips, slides and prints, manuscript project files, training materials, administrative records, and born-digital files. The grant work will focus on the digitization and transcription of the oral histories, scanning of the photographic materials, and sharing the collection’s contents with students, educators, and the wider public through virtual programs and webinars. The digital collection will be published in the Duke Digital Repository, where 410 BTV interviews are currently accessible for research. Funds will also allow the project team to hire graduate level interns for archival processing, digitization, and outreach.

John B. Gartrell, director of the John Hope Franklin Research Center and principal investigator for the grant noted, “The Behind the Veil collection is one of the most used collections in the Franklin Research Center. These oral histories truly broaden our understanding of the everyday lives of African Americans during the early-to-mid twentieth century. They represent one of the largest bodies of scholarship on African American life documenting that time, and I’m excited to share the depth of these stories and honor the scholars who recorded them.” Gartrell will be joined by co-principal investigator Giao Luong Baker, who serves as Duke Libraries’ Digital Production Services Manager. Together they will lead the digitization efforts in collaboration with library colleagues over the course of the next three years (2021–2024).