Post contributed by Matthew Farrell, Digital Records Archivist.

At the University Archives, we work hard to dispel the stereotype that we are merely reactive documenters of Duke’s history, that we wait to receive evidence of activity reflected in the records of the offices, organizations, and bodies that donate or transfer materials to us. We pursue student organizations‘ materials and meet regularly with representatives from both transitory and permanent bodies active in the Duke community. Since 2010, we have selectively crawled websites related to Duke.

The recent activism on campus has given us the opportunity to try new methods of documentation. Students and protesters disseminated much of the information related to the Allen Building Sit-In staged by Duke Students & Workers in Solidarity (DSWS) and ongoing tenting on the Abele Quad on Twitter, Instagram, and other web platforms. The Chronicle published a lot of coverage in print issues of the paper, but created multimedia presentations online and on Twitter. What follows are some of the methods we used to approach capturing online materials related to student activism, brief summaries of how well we did, and some early thoughts on what our responsibilities are with respect to access and re-use of this material.

We used three tools to primarily collect web materials, each with its own strengths. The Rubenstein Library subscribes to the Internet Archive’s Archive-It web crawler, which allows us to execute captures of web pages. I wrote about our broader efforts around Archive-It and Duke History last year on this blog. Archive-It is best suited for more static websites, and is less effective at capturing dynamic conversations. For the recent student activism, Archive-It came in handy when capturing the website of the DSWS, as well as the ongoing, related criticism of campus culture at Duke by the #DukeEnrage collaborative.

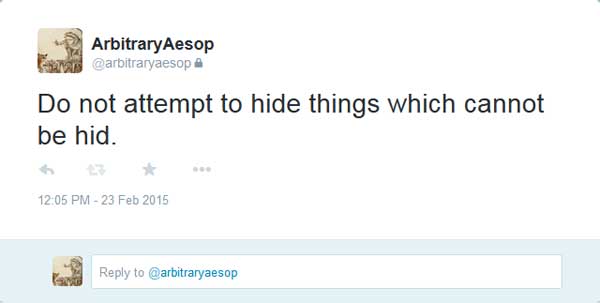

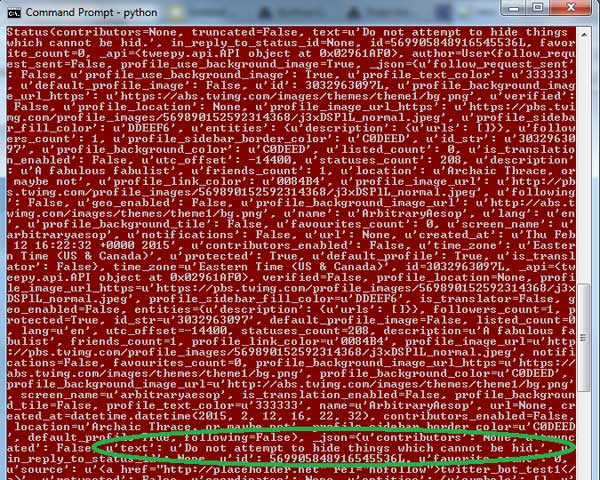

Archive-It has some capability for capturing Twitter, but it’s Twitter as viewed on Twitter.com: it’s a flat presentation of a Twitter feed or search. Here is a comparison of a tweet presented by Twitter, and what it looks like in its raw form.

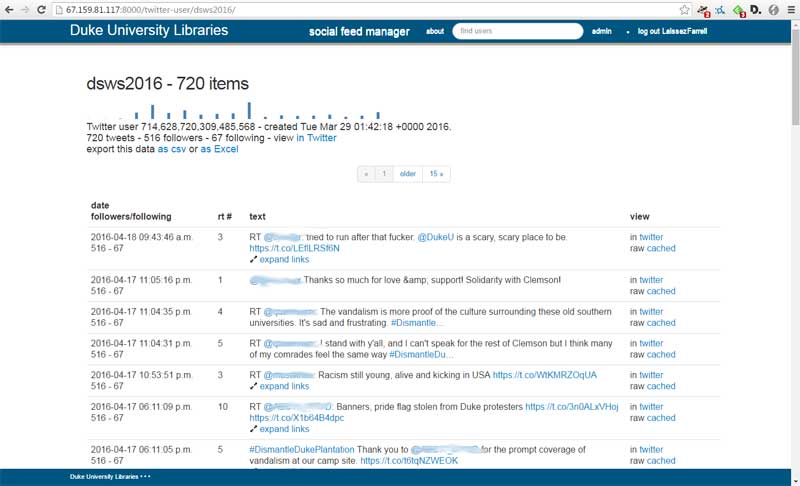

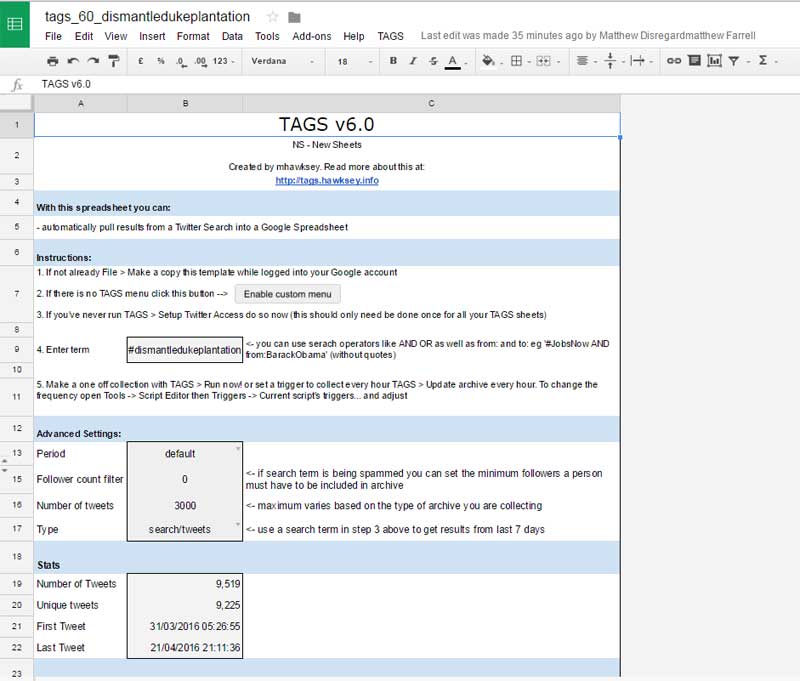

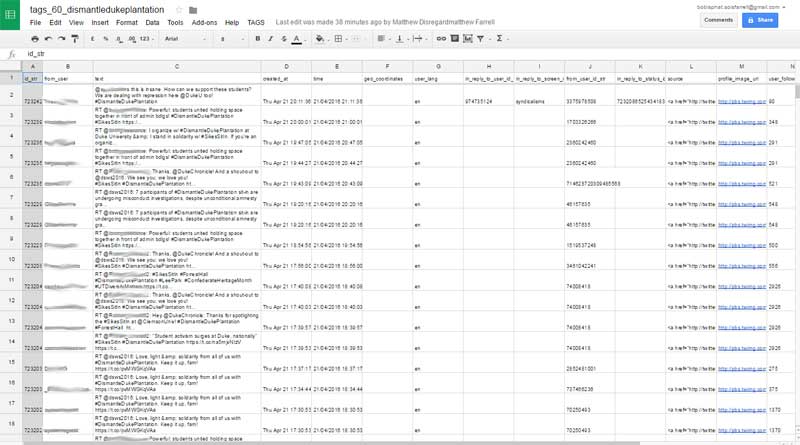

This lack of flexibility influenced our decision to look elsewhere for capturing Twitter. We settled on two applications: Social Feed Manager and Twitter Archive Google Spreadsheet (TAGS). Both tools, once configured, query the Twitter API, retrieve tweets in their native form, and do some level of processing on them. Social Feed Manager stores tweets and allows the user to export them as a CSV or Excel file for offline storage. TAGS parses tweets into a Google Sheet, which can be downloaded for offline storage. For logistical reasons, we chose to use Social Feed Manager in the rare occasion of attempting to capture the tweets of an entire account—in this case, the @dsws2016 account.

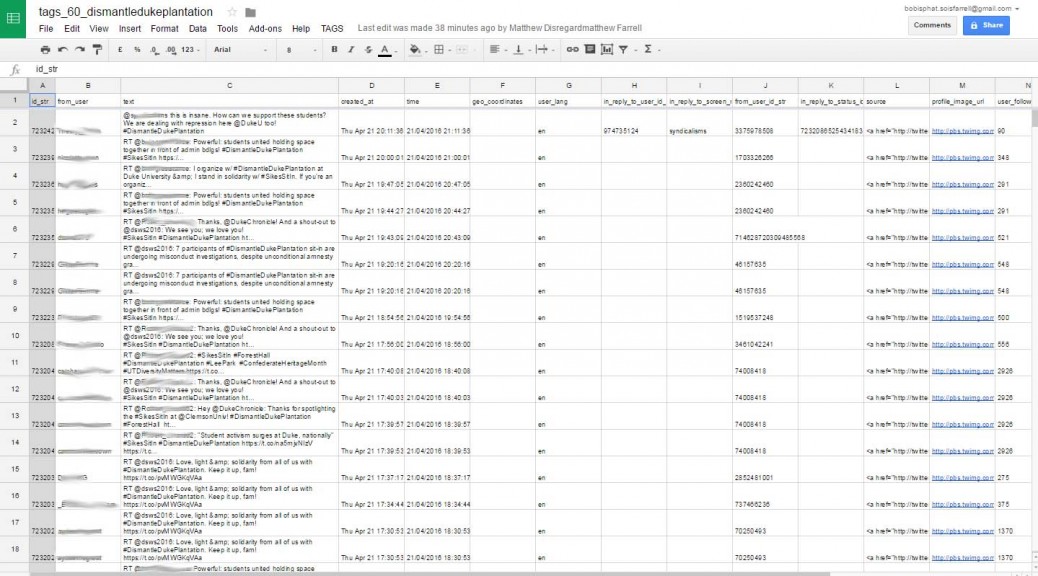

We used TAGS to crawl hashtags. Since November, we had been capturing tweets related to #DukeEnrage, #DUBetter, and #DukeYouAreGuilty. Once the Allen Building Sit-in began, we added #DismantleDukePlantation and #DukeOccupation2016. Most of these were relatively low-use hashtags, with one exception: use appears to have coalesced around #DismantleDukePlantation, resulting in around 7000 unique tweets from the week of the sit-in, and another 2000 from the time since.

This work is still ongoing. So far, I think of our efforts as a modest success. The web, and especially social media, is ephemeral (although, oddly and wonderfully, aspects of the web we thought would disappear have persisted). That said, these efforts represent only one or two angles into the online conversation. Newer platforms like Yik Yak and Snapchat are either location based or expose content only temporarily. The tools available to capture Instagram are not as developed as those for Twitter. We cannot, nor do we want to, capture everything.

There are also questions of ethics and access. We received (enthusiastic, as it happens) permission from students associated with DSWS to capture their Twitter feed*. It would be impossible to seek permission from each individual Twitter user who tweeted using #DismantleDukePlantation. Although everything we targeted is still currently available through Twitter, the users who created it likely did not expect it to be re-contextualized—even if they fully understood the terms of service they clicked through when they signed up for the service. Twitter would frown upon us releasing material we captured through the API on the open web. For the time being, we tentatively plan on making the Twitter content available in our reading room, though we would need to consider anonymizing the data first.

This is by far not the only arm of our effort in documenting recent and ongoing student activism on campus. We fully expect for administrative records from relevant University offices to be transferred to the University Archives. We have been in touch with classes interested in further documenting the student voices involved. Selectively capturing Twitter and crawling static web pages allows us to capture student activists and their activities in the moment

*[edit] A former University Archives student worker, responsible for outreach in DSWS, granted UA explicit permission to capture the group’s Twitter and Facebook content.