This month on the 1091 Project we talk about how we make treatment decisions. Treatment decisions are based on a conservator’s experience with materials, knowledge of treatment options, and understanding of the object as it relates to the collection.

This month on the 1091 Project we talk about how we make treatment decisions. Treatment decisions are based on a conservator’s experience with materials, knowledge of treatment options, and understanding of the object as it relates to the collection.

Treatment Goals

Conservators must balance the item’s value to the collection, how and how much it has been or will be used, and to what extent the binding and its contents are at risk for further loss or damage. For any item in the lab we have a few overarching treatment goals:

- Save as much of the original as possible

- Use reversible repair methods as much as possible

- Use high quality repair materials and adhesives

- Repairs should not be stronger than the weakest part of the original

- Create a sympathetic repair that does not obscure the fact that it was done (conservation vs. restoration)

- The repair should facilitate use of the item

From there we ask:

- Can we do it?

- Should we do it?

- How should we proceed?

There is an entire chapter to write just about this section, but let’s move on to the process of making a treatment decision for one book from our general (circulating) collections workflow.

Condition Review

Transactions of the Zoological Society of London, volume VI (London, 1869)

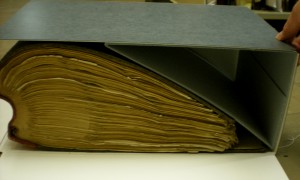

This book came to the lab because someone used packing tape to repair the damaged spine. The fragile leather binding tore off the book as a result.

The binding is a hollow-back binding in quarter leather with tight joints. The leather is weakened and failing; the marbled papers over the boards are abraded; the corners are worn; the spine and boards are off the text block; and the spine has been heavily taped with fresh packing tape, the carrier and adhesive are present, and the adhesive is very sticky.

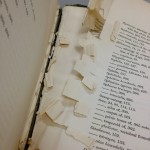

The text block is made with wove paper and is borderline brittle and oversewn; the paste downs and flyleaf have detached; the spine adhesive and linings are intact; the sewing is intact except for the first and last few pages; the printer’s ink is stable; there are foldouts, some of them are misfolded with damaged edges; several pages at the front and back have multiple tears.

Treatment Options

Can we do it?

The two biggest problems with this book are the tape and the oversewing. If removed, the adhesive on the packing tape will take the fragile, thinly-pared leather with it resulting in a time consuming repair. Oversewing creates a very inflexible spine that restricts the opening and puts tremendous stress on the first few pages, resulting in breaks at the bound edge that are difficult to repair because of the stitching. The fastest, most economical and most practical option may be to replace the binding, but the oversewing will continue to be problematic.

The borderline brittle paper worries me. Because they are stronger than the substrate, repairs can provide a breaking edge for brittle paper. Although this paper is slightly brittle, it still has some flexibility. I think we can repair the page tears and fold-outs but it will take a lot of time.

Should we do it?

The information in this book is likely more valued than the binding by researchers. This book has only five circulations on its record. I could check with the biology librarian whether this may be a faculty favorite, it seems likely that it is.

The new binding and paper repairs will take an estimated 3-4 hours of bench time. I have one technician for the entire general collections workflow (5+ million books). Is this one book worth repairing three or four others that may have higher circulation records? Good question.

We can defer the treatment until its next use. All the parts are here, and though the boards and some pages are detached the book can be carefully used. We could make a protective enclosure (about 15 minutes of time) and put it back as-is if we think that its future use is likely not going to be high.

How should we proceed?

Readers, what do you think? Weigh the issues and options and leave your thoughts in the comments. Head over to Parks Library Preservation to find out how they make decisions.

We have been so busy with renovation projects that we forgot that today was a scheduled 1091 post. Instead of a long, thoughtful expose on a current conservation topic, Melissa and I will share some images of what is happening in our labs today. Think of it as a glimpse behind the scenes.

We have been so busy with renovation projects that we forgot that today was a scheduled 1091 post. Instead of a long, thoughtful expose on a current conservation topic, Melissa and I will share some images of what is happening in our labs today. Think of it as a glimpse behind the scenes. Bonus pic: Look what showed up in my mailbox! A wonderful, home-made pop-up note to thank me for some consultation I did for someone whose cat damaged some of their papers.

Bonus pic: Look what showed up in my mailbox! A wonderful, home-made pop-up note to thank me for some consultation I did for someone whose cat damaged some of their papers.