A damaged binding can present the opportunity to examine the interior structure and composition of a book without the use of advanced imaging equipment. This copy of Durandus of Saint-Pourçain‘s four books of commentaries on the Sentences of Peter Lombard from 1539 offers an interesting look at some common elements of early book structure. Many books from this period have been rebound or drastically altered over the years, so objects like this are quite exciting to examine in detail.

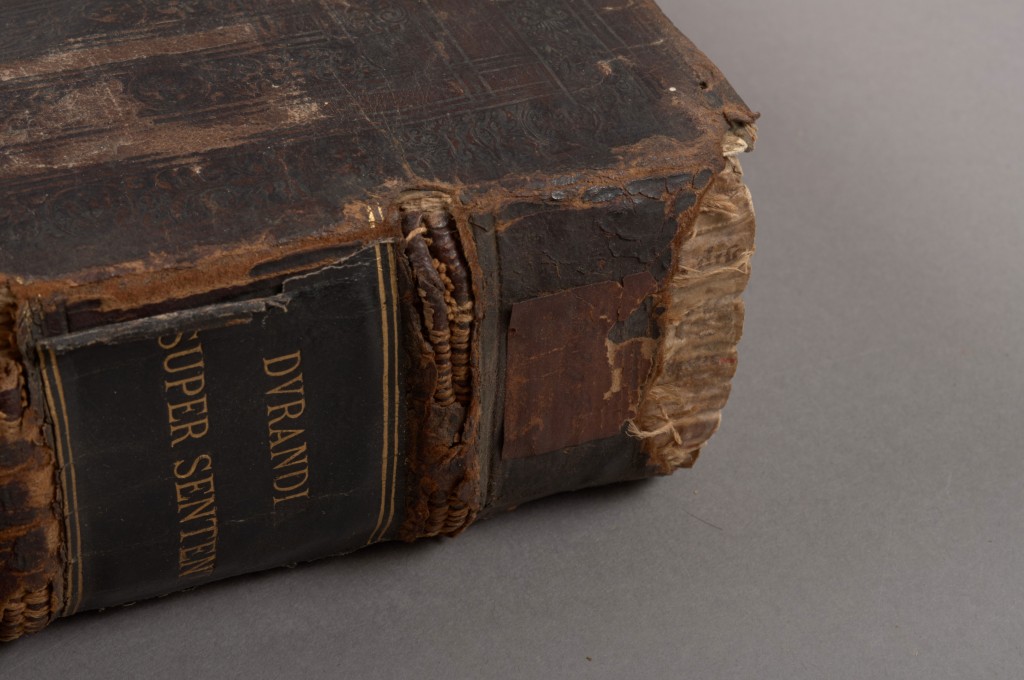

The binding is fully covered in brown tanned leather, tooled in blind over the boards in a multi-panel design that is common for the period.

You may be able to make out the first few letters (“DVRAN”) of the author’s name written on the fore-edge of the textblock in ink, which probably served as the original titling. Early storage and labeling practices for books were very different from the upright, spine-facing-out shelving method we use today. Henry Petroski, Professor of Civil Engineering at Duke, has a wonderful book on design and book storage, titled The Book on the Bookshelf, which describes this in more detail. I highly recommend it.

Two labels were later applied to the spine of the volume. In the image below, you can see the remains of a paper label in the top spine panel and a leather label in the second panel. Some of the damage here offers an interesting glimpse into the structural elements of the binding. The textblock was sewn on double raised supports of twisted leather, rather than vegetable cord. The sewing pattern is pretty clearly visible here. Damage to the headcap has exposed a spine lining of parchment manuscript waste, as well as the tie-down threads of the sewn headband.

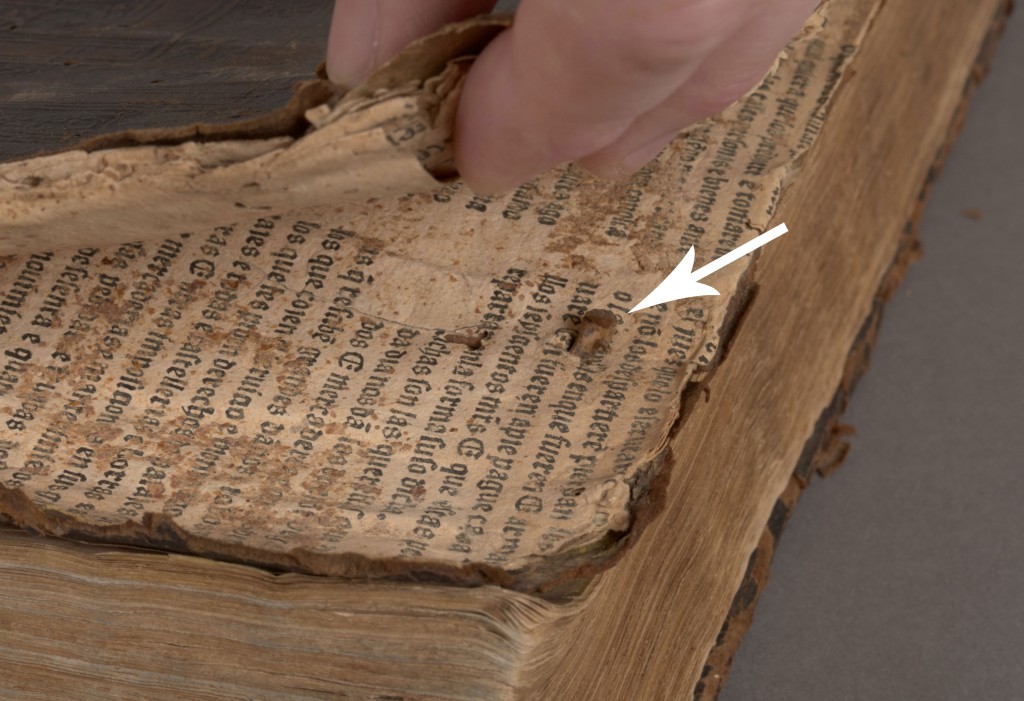

The most interesting part of this binding (for me at least) is the boards. It is common to see 16th century bindings with thick wooden boards, but this is a nice example of early pasteboard, a technique for making stiff board by laminating pieces of paper together with adhesive (Etherington & Roberts, 1982). Pasteboards tend to be much softer and more flexible than other types of book board. The adhesive between many layers of the paper has failed and the leather has split all around the edges of both boards, so the boards now freely “open” in places and allow a look inside.

In the image above, you can clearly see some of the print waste which was used to make up the board. You can also see the remains of two leather fore-edge ties, which laced through the boards. While the the majority of that leather tie has broken off and is now gone, the ends are visible inside the board and through the rear pastedown (blue arrows below). You can also clearly see the holes where they exited the boards in the image of the front cover near the top of this post.

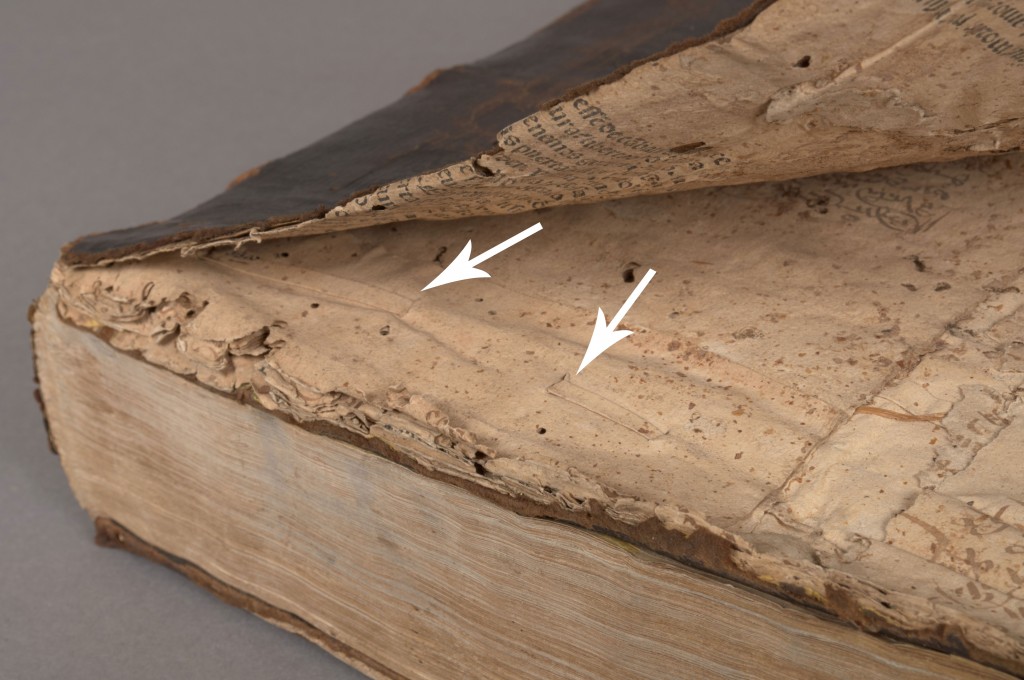

Both print and manuscript waste are visible in the exposed layers of the front board, but there is another very interesting element here: The arrows in the image below point to a thin strip of paper, which laces through one of the board’s constituent sheets. I cannot say for certain, but this could be part of a laced paper binding, which got chopped up and added to the pasteboard.

While the condition issues of this binding present a risk of further damage and loss, they also provide the opportunity to learn more about its structure and means of production. These raise some interesting questions about the best approach for treatment and rehousing, and will inform our discussions with the curators.