In the Assessment & User Experience Department, we’re always looking for ways to improve how our patrons experience the libraries’ physical and online spaces. One of our primary ways of learning about our patrons is our biennial user satisfaction survey, which we use to collect opinions from large groups of our patrons about a wide range of issues.

One topic that comes up regularly among our patrons is the navigation of our physical spaces. Like many libraries, our buildings have evolved over time, and that can make navigating our spaces a bit complicated. On Duke’s West Campus, we have three library buildings that are interconnected – Rubenstein Library, Perkins Library, and Bostock Library. Responses and comments on our biennial survey confirm what we hear anecdotally – patrons have trouble navigating these three buildings.

Deep Dive into Navigation Concerns

But how can we follow up on these reports to improve navigation in our spaces? Ideally, we would gather data from a large number of people over a long period of time to find very common and problematic navigation issues. Our biennial survey offers data from a large number of people over time, but it isn’t a great format for gathering detailed data about narrow subjects like navigation. Conducting an observational study of our spaces would explore navigation directly, but it would only include a small number of people, and the likelihood that we would catch individuals having trouble with navigation is low. We could try conducting ad hoc surveys of patrons in our spaces, but it would be difficult to ensure we are including people who have had navigation trouble, and it may be difficult for patrons to recall their navigation trouble on the spot.

What we needed was a way of capturing common examples of patrons having trouble with navigation. We decided that, instead of asking patrons themselves, our best resource would be library staff. We know that when patrons are lost in our buildings, they may reach out to staff members they see nearby. By surveying staff instead of patrons, we take advantage of staff who know the buildings well and who are commonly in particular areas of the buildings, noticing and offering help to our struggling patrons.

We decided to send a very simple survey to all staff in these library buildings. Staff could fill it out multiple times, and the only two questions were:

- What is a common question you have helped patrons with?

- Where are the patrons when they have this question, typically?

We had a great response from staff (72 responses from 36 individuals), and analyzing the responses showed several sources of confusion.

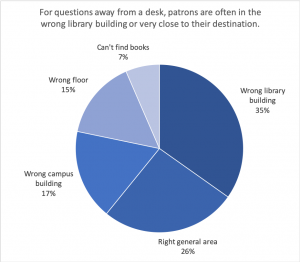

Focusing on questions where patrons are in library spaces and not near a help desk, two concerns account for over 60% of reported patron navigation issues:

- Building confusion

- Hidden rooms

Trouble Between Buildings

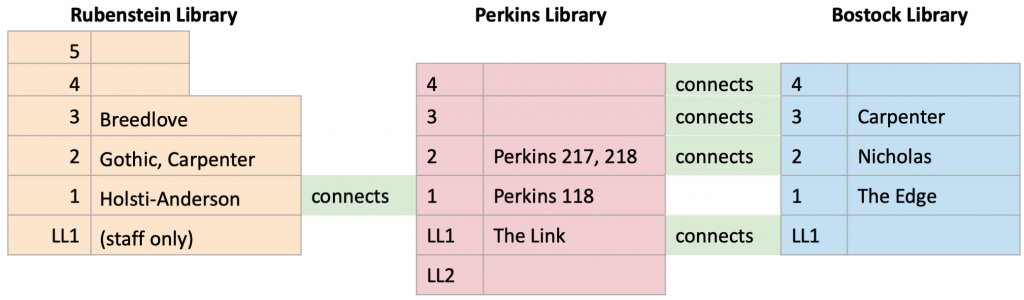

Our three connected library buildings, unfortunately, connect in ways that are not obvious to new visitors. Because buildings only connect on certain levels, it is easy for patrons to be looking for a location on the right floor but the wrong building. By asking staff for specific locations of both patrons and their desired destination, we could compile the most frequent problems that involve being in the wrong building. Unsurprisingly, the locations that cause the most difficulty are our large meeting rooms and classroom spaces, especially those that are not on the ground floor of the buildings.

The most common problems seem to happen when patrons leave the first floor while in the wrong building, expecting the buildings to connect on the other floors (or not realizing which building they are in). As you can see from the side-view of our buildings below, the Perkins and Bostock library building have easy connections on all floors, but the Rubenstein Library only connects to Perkins on the first floor. Our survey confirmed that this causes many issues for patrons looking for 2nd floor or Lower Level meeting rooms in Perkins and upper level meeting rooms in Rubenstein.

While we are still in the process of developing and testing possible solutions, we hope to redesign signage in a way that better signposts when patrons should proceed onward on the current floor and when they should transition up or down.

Trouble on the Same Floor

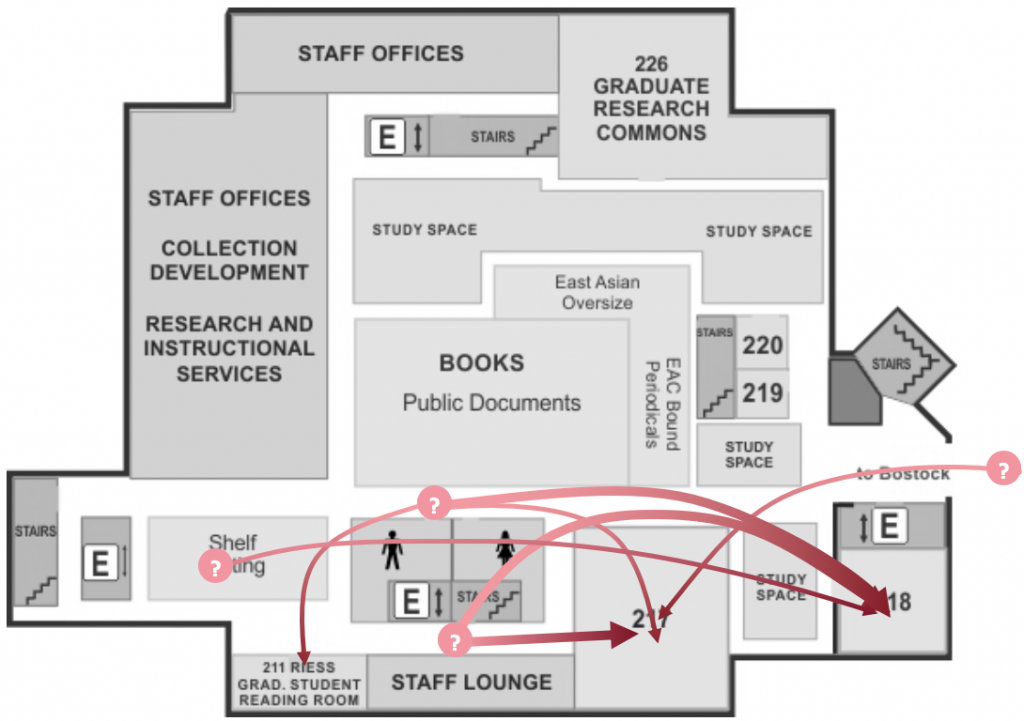

Our survey suggests, unfortunately, that it is not enough to get patrons to the correct floor. Depending on the route the patron takes, there are still common destinations that are difficult to see from stairwells, elevators, and main hallways. Again, this difficulty tends to arise when patrons are looking for meeting rooms. This makes sense, as events held in our meeting rooms can attract patrons who have not yet been to our buildings.

Staff reports for same-floor confusion focus largely on floors where room entrances are hidden in recesses or around corners and where rooms are spaced apart such that it is hard to simply follow room number signage. As a notable example, the 2nd floor of Perkins Library seems especially confusing to patrons, with many different types of destinations, few of which are visible from main entrances and hallways. In the diagram below, you can see some of the main places patrons get lost, indicating a need for better signage visible from these locations. (Pink question marks indicate the lost patrons. Red arrowheads indicate the desired destinations.)

As we develop solutions to highlight locations of hidden rooms, we are considering options like large vinyl lettering or perpendicular corridor signs that alert people to rooms around corners.

Final Thoughts

This technique worked really well for this informal study – it gave us a great place to start exploring new design solutions, and we can be more proactive about testing new navigation signage before we make permanent changes. Thanks for your great information, DUL staff!

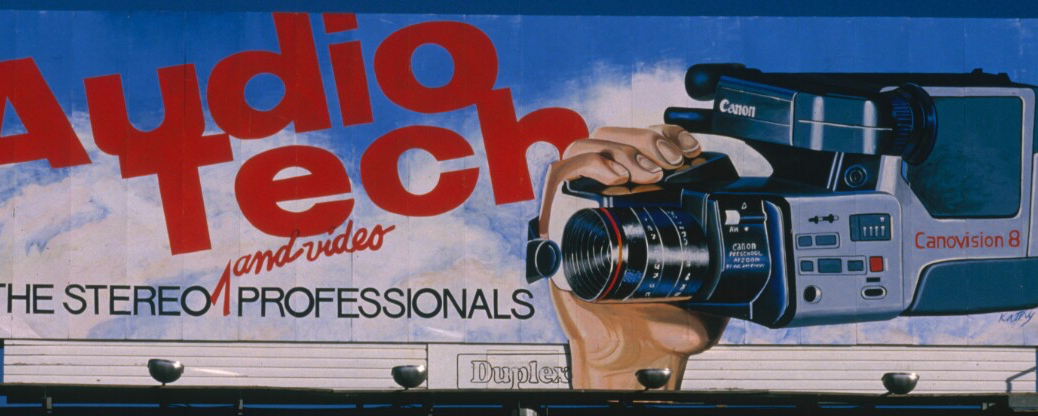

Once the shot is in focus and appropriately bright, we will check our colors against an X-Rite ColorChecker Classic card (see the photo on the left) to verify that our camera has a correct white balance.

Once the shot is in focus and appropriately bright, we will check our colors against an X-Rite ColorChecker Classic card (see the photo on the left) to verify that our camera has a correct white balance.