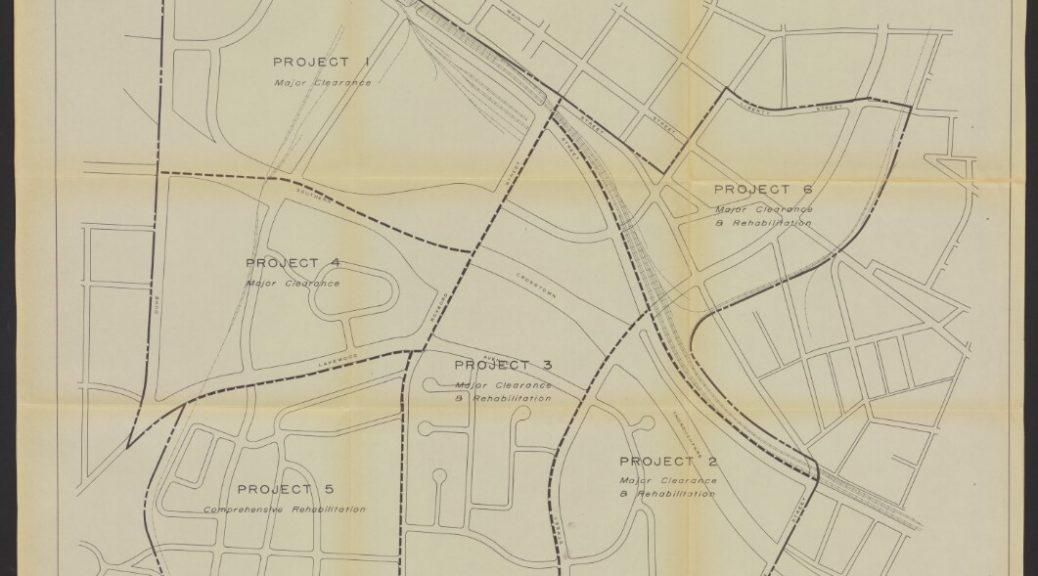

In 2019, one of the digital collections we made available to the public was a small set of architectural maps and plans titled the ‘Hayti-Elizabeth Street Renewal Area’. The short description of the maps indicates they ‘depict existing and proposed structures and modifications to the Hayti neighborhood in Durham, NC.’ Sounds pretty benign, right? Perhaps even kind of hopeful, given the word ‘renewal’?

Nope. This anodyne description does not tell the story of the harm caused by the Durham Urban Renewal project of the 1960s and 1970s. The Durham Redevelopment Commission intended to eliminate ‘urban blight’ via this project, which ultimately resulted in the destruction of more than 4,000 households and 500 businesses in predominantly African American areas of the city. The Hayti District, once a flourishing and self-sufficient neighborhood filled with Black-owned businesses, was largely demolished, divided, and effectively severed from what is now downtown Durham by the construction of NC Highway 147.

Bull City 150, a “public history, geography and community engagement project” based here at Duke University, hosts a suite of excellent multi-media public history exhibitions about housing inequality in Durham on its website. One of these is Dismantling Hayti, which focuses in particular on the effects of urban renewal on the neighborhood and the city.

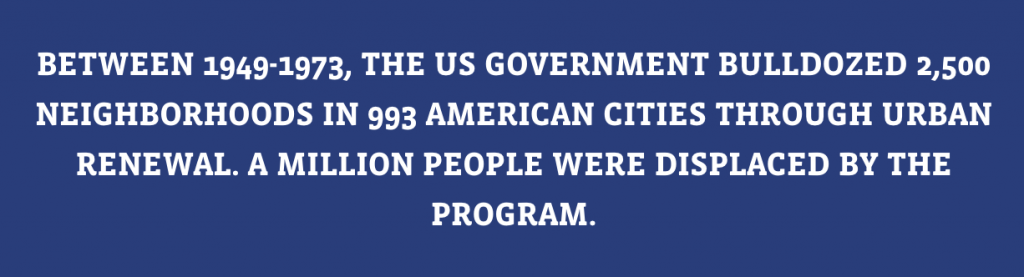

But this story of so-called urban renewal is not just about Durham – it’s about the United States as a whole. From the 1950s to the 1980s, municipalities across the country demolished roughly 7.5 million dwelling units, with a vastly disproportionate impact on Black and low-income neighborhoods, in the name of revitalization. Bulldozing for highway corridors was frequently a part of urban renewal projects, happening in San Francisco, Memphis, Boston, Atlanta, Syracuse, Baltimore, everywhere in the country – the list goes on and on. And it includes Saint Paul, Minnesota, the city where, mourning and protesting the killing of yet another Black person at the hands of a white police officer, thousands of people occupied Interstate 94 in recent weeks, marching from the state capitol to Minneapolis, over a highway that was once the African American neighborhood of Rondo.

Urban renewal projects led to what social psychiatrist Dr. Mindy Fulilove refers to as root shock – “a traumatic stress reaction related to the destruction of one’s emotional ecosystem”. This is but one thread in the fabric of white supremacy out of which our country was woven, among other twentieth century practices of redlining, discriminatory mortgage lending practices, denial of access to unemployment benefits, and rampant Jim Crow laws, which are still causing harm today. This is why it is important to interrogate the historical context of resources like the Hayti-Elizabeth Street Renewal Area maps – we should all accept the invitation extended on the Bull City 150 website to Durhamites to “reckon with the racial and economic injustices of the past 150 years and commit to building a more equitable future”.

Once the shot is in focus and appropriately bright, we will check our colors against an X-Rite ColorChecker Classic card (see the photo on the left) to verify that our camera has a correct white balance.

Once the shot is in focus and appropriately bright, we will check our colors against an X-Rite ColorChecker Classic card (see the photo on the left) to verify that our camera has a correct white balance.